Pancreatic Microbiome May Hold the Key To Better Treatment

Nothing has caught the fancy of the health-conscious as much as our guts.

Specifically, our gut microbiome, that rich population of tens of trillions of microorganisms that we hope to keep healthy with prebiotics and probiotics found in foods and supplements.

After all, why not? The microbiome has been linked to a lot of things that keep us functioning, like digestion and a healthy immune system. But the human microbiome is more than just our intestinal tracts. A lot more. The human microbiome is actually the genetic material of all the microbes (bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses), the so-called “bugs” that live on and inside the human body. Our skin has a microbiome. So do our lungs. The mouth is a hotbed of microorganisms, as is the pancreas.

“People generally think of the pancreas as this very sterile organ, but we now know that isn’t true,” explains medical oncologist Dr. Deirdre Cohen, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, and Director, Clinical Trials Office at NYU Langone Medical Center’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, in New York. In fact, research conducted at NYU Langone found that gut bacteria can migrate to the pancreas and may directly influence the pancreatic cancer microenvironment. The hope is that as researchers find out more about our pancreatic bugs, they may be able to find and hone effective treatments for pancreatic cancer and maybe even devise an early-warning system for the disease.

Unique Microbiome Findings Lead To Pilot Study

The NYU Langone team is now ready to start a multi-center, single arm, open-label pilot window of opportunity study of preoperative antibiotics and pembrolizumab (brand name Keytruda). Pembrolizumab is a type of immunotherapy, specifically a checkpoint inhibitor, which is approved for many different types of cancers, including advanced non-small cell lung cancer, classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, advanced gastric cancer, advanced melanoma, microsatellite high instability cancer (which includes some pancreatic cancers), and other cancers. It works by blocking a specific pathway called PD-1, which makes cancer cells more visible to the immune system.

The researchers have reason to be hopeful that this study will show a signal of efficacy since their earlier work, which was recently published in the journal Cancer Discovery, revealed some unique findings about the pancreatic microbiome.

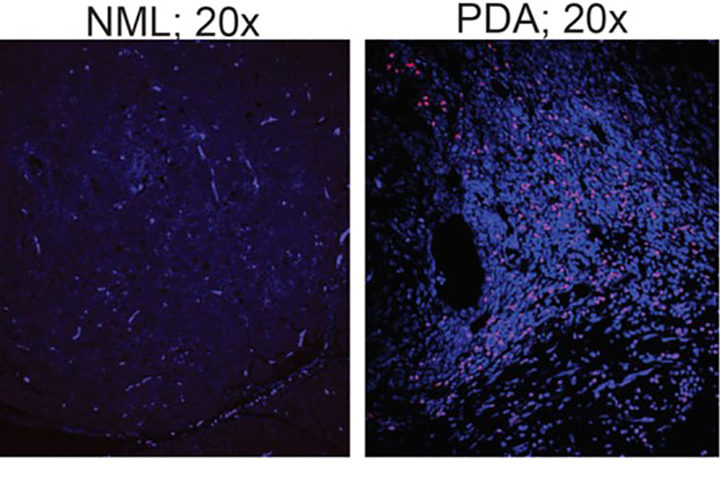

The team showed that the population of bacteria in the pancreas increases more than a thousandfold in patients with pancreatic cancer, and becomes dominated by species that prevent the immune system from attacking tumor cells. But removing bacteria from the gut and pancreas by treating mice with antibiotics slowed cancer growth and reprogrammed immune cells to again better identify cancer cells.

In fact, oral antibiotics increased the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors by about threefold. “Checkpoint inhibitors have worked very well in other cancers, and they have helped some pancreatic cancer patients, unfortunately not many,” says Cohen. She explains that checkpoint inhibitors work by releasing a natural brake on your immune system so that immune cells called T cells recognize and attack tumors. “We’re hoping to make these checkpoint inhibitors more effective, and looking at the pancreatic microbiome makes a lot of sense,” she adds.

To further show that bacteria from the gut can populate the pancreas, fecal samples from 32 patients with pancreatic cancer were compared to fecal samples of 31 healthy people. Gut microbiota in healthy people and those with pancreatic cancer had large populations of two similar types of bacteria called Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. But other types, specifically Proteobacteria, Synergistetes, and Euryarchaeota, were much more abundant in patients with pancreatic cancer. The researchers hope this finding could eventually be used as a kind of biomarker for potential pancreatic cancer.

Early-Stage Patients Eligible

Patients with stage I and II resectable pancreatic cancer (defined by National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines 1.2018) are eligible for the pilot study. All participants will undergo baseline tumor, blood, and stool collection. Patients will receive a seven-day lead-in of antibiotics with ciprofloxacin and metronidazole (two common antibiotics) in order to target gram-negative and anaerobic bacterial species. Pembrolizumab will be given for two doses every three weeks starting on day eight. Antibiotics will continue throughout the entire four- week preoperative period. Blood will be collected weekly as part of the study. Stool will also be collected weekly during the treatment phase.

“What we want to figure out is if there is actually a change in immune activation after treatment with these antibiotics and the checkpoint inhibitor,” explains Cohen, adding that establishing the safety and feasibility of preoperative antibiotics in combination with immunotherapy are also objectives.

“Small studies like this with translational endpoints are really extraordinarily helpful because if we do see a signal we can look quickly at creating a ‘version 2.0’ where we can better determine optimal antibiotic regimens and maybe even combining antibiotics with probiotics,” she says. “What we want to find is the perfect cocktail for the best immune response.”

“I think the microbiome may hold some answers.”