A Newly Identified Biomarker Panel Shows Promise in Earlier Pancreatic Cancer Detection

While there have been some strides made in the treatment of pancreatic cancer, the majority of patients are diagnosed at later stages of the disease when treatment is less effective.

That’s why researchers across the globe have been looking for ways in which pancreatic cancer may be found earlier. It has been a persistent scientific challenge.

However, a new study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine shows that a pair of biomarkers in the blood picked up pancreatic cancer in human cancer cells at different stages of tumor growth. This new finding is providing scientists—and patients—with new hope in the challenge of finding the disease before it has spread, and perhaps even before pancreatic cancer develops into early-stage disease.

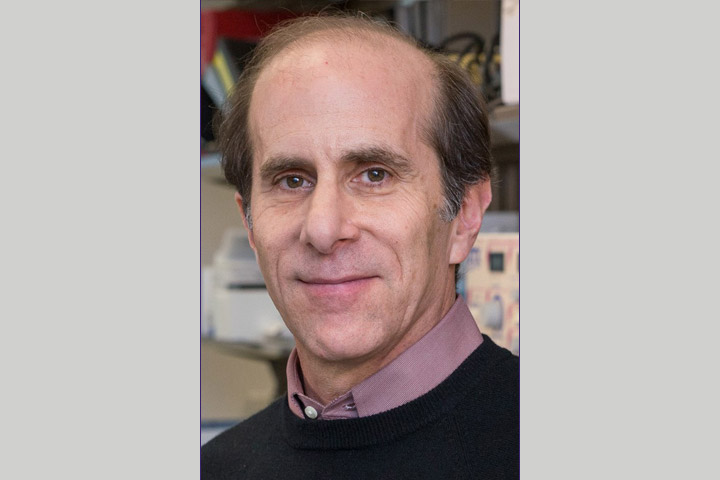

“Although we are still early in the process, the test needs to be refined and more trials need to be done. I am excited about this both from a scientific and academic perspective, but also and most importantly, for the patients that may eventually be helped,” says study co-author Dr. Ken Zaret, director of the Penn Institute for Regenerative Medicine and the Joseph Leidy Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology.

The two-pronged biomarker panel includes plasma thrombospondin-2 (THBS2), which was combined with a known later-stage biomarker called CA19-9. Together, these biomarkers had 87 percent sensitivity, meaning that’s how often they can correctly identify someone with stage I or II pancreatic cancer. They also had 98 percent specificity, meaning the combination test could accurately rule out cancer in a person who doesn’t have it.

“This biomarker panel is inexpensive and it’s conventional so it could be performed at diagnostic centers pretty easily,” Zaret says.

A Meticulous Process

The study involved a meticulous, multi-step process that included the identification of potential biomarkers followed by work to confirm whether these potential biomarkers could accurately identify cancer.

Identification of these biomarkers is no easy task. But with expertise in genetics and stem cell biology, Zaret took late-stage pancreatic cancer cells and reprogrammed these cells into a state similar to embryonic stem cells. These cells were then able to differentiate, or change, and progress from early to late stage pancreatic cancer.

“The thought was that if we could take a late-stage cancer cell and make it into an early stem cell, there was a chance it would redevelop the cancer, undergo a progression, and basically not go into a late-stage right away,” Zaret said, adding that much biomarker researcher has been focused on late-stage pancreatic cancer tissue provided post-surgery. “You work with what you get, but I didn’t think this was a good approach to finding early-stage markers,” he said.

The next step involved looking for proteins that are found in low levels in our blood. One of those proteins was THBS2, which was elevated in blood samples from 81 pancreatic cancer patients compared to a control group of 80 people without the disease.

But the results of this phase needed more fine-tuning in terms of sensitivity and specificity. So the researchers combined THBS2 with CA19-9, which has been shown to be a sensitive marker for pancreatic, gastric, and hepatobiliary malignancies, such as cancer of the liver, bile ducts, and biliary tract. During this phase, the researchers analyzed samples from 197 cancer patients, a control group of 140 people without pancreatic cancer, and 200 people with pancreatic problems that weren’t linked to cancer.

It was this combination that increased the test’s accuracy.

The Next Step

The investigators now plan to test and validate blood samples collected from pancreatic cancer patients before they were diagnosed. The hope is the test could eventually be used in pancreatic cancer patients and individuals with a high risk for developing the disease, such as first-degree relatives, those with a genetic predisposition, or people with a sudden onset of diabetes after age 50.

What Zaret hopes is the test will eventually be refined enough to find pancreatic cancer even before it reaches stage I, which has a five-year survival rate of about 12 to 14 percent.

“I remember a surgeon telling me once that you want to be able to find pancreatic cancer even before a patient even needs to have surgery, so our goal would be to find it at stage minus one,” says Zaret, adding that additional studies and clinical trials that will test the approach in high-risk individuals are already being planned.

“If doctors can find the pancreatic cancer earlier there is the hope of higher survival rates,” he says. “And if we can find it before it’s even stage I, when people are on the path to developing pancreatic cancer, who knows what new therapeutics could come along and change their lives.”