The Anatomy of a Whipple Procedure

It’s an unassuming gland with a wide head, tapering body, and a narrow, pointed tail that rarely makes itself known: the pancreas.

Most people don’t get to know this organ until it causes trouble. Roughly the size of a medium banana, it is located deep in the abdomen, nestled in the curve of the small intestine and sandwiched between the stomach and the spine. In this way, it avoids notice, and often medical imaging and intervention.

In order to operate on the pancreas, surgeons must first uncover it. This often involves moving the organs in which it nests, as well as two very important blood vessels that crisscross it, the superior mesenteric artery and the superior mesenteric vein.

A pancreatoduodenectomy, commonly referred to as the Whipple procedure in honor of the New York physician who perfected it, Allan Whipple, is famously complicated and demanding surgery that takes anywhere from four to 12 hours to complete. A quick anatomy lesson will make it clear why.

Two Roles, One Organ

The pancreas has a dual function. It is an organ of both the hormonal (endocrine) and digestive (exocrine) system.

Many people are familiar with the pancreas because of its hormonal role, and have probably heard it referred to in association with diabetes. It produces the hormone insulin, which helps to control the amount of sugar in the blood.

But the pancreas is also important in digestion. Once food has been broken down and partially digested by the stomach, it is pushed into the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum. The pancreas then adds its own digestive juices and enzymes to the food, via a small duct attached to the duodenum.

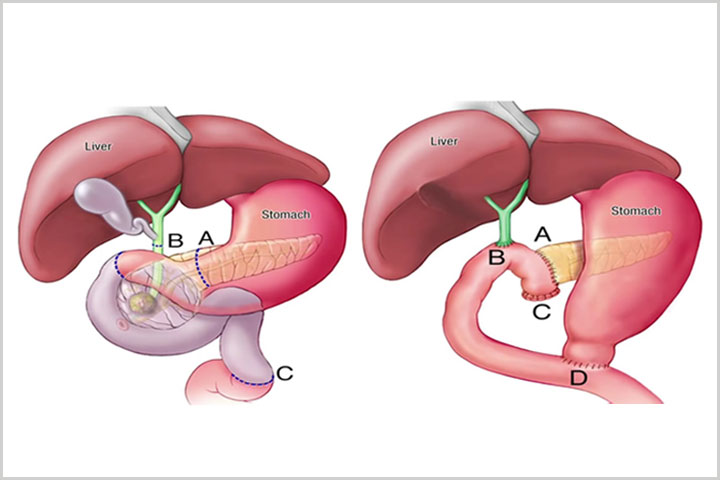

Because of the pancreas’ functional and locational connections to the stomach, intestine, and bile duct, the Whipple procedure is more than just an operation on the pancreas: it involves at least three other organs as well.

Dr. Horacio Asbun of the Miami Cancer Institute, Florida (and formerly with the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville), explains that surgeons remove the head of the pancreas (site A), the bile duct and gall bladder (site B), the beginning of the small intestine (site C), and often at least part of the stomach (site D). Depending on the site and state of the tumor, the mesenteric artery and vein may also need to be moved, further complicating the surgery.

The surgeon then reconnects the remaining parts of the pancreas, intestine, and stomach. The video from the Mayo Clinic explains the surgery in detail.

Full removal of the pancreas, known as total pancreatectomy, is also possible, but by preserving enough of the organ to maintain the production of insulin and digestive juices, Whipple patients face fewer metabolic complications. Surgeons will also try to preserve the pylorus (which connects the stomach and duodenum) if there is no sign of disease there, as it plays an important role in digestion, acting as a valve that controls the flow of partially digested food from the stomach to the small intestine.

Ways to Whipple

Due to difficulties in imaging the pancreas, many surgeons are not sure what they are facing until they operate, so many opt for open procedures in which they make a large incision in the abdomen to access the internal organs.

Laparoscopic surgery is also available, with the benefit of smaller incisions and quicker recovery times. But it can be difficult due to limited ergonomics and only two-dimensional images of the crowded organ area.

The recent addition of robotic equipment has made minimally invasive “keyhole” surgical approaches more popular, providing better magnification and three-dimensional vision, and improved surgical precision and dexterity through the use of wristed laparoscopic instruments that mimic human hand movements.

At UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, where surgeons have performed more than 500 robotic-assisted Whipples, surgical oncologist Amer H. Zureikat explains that the advancement has broadened the range of pancreatic cancer patients who can be considered candidates for surgery. It can also indirectly affect other treatments.

“Robotic Whipple surgery is a potential game changer because it reduces recovery time and may restore health quicker so that other treatments needed to improve survival after surgery—like chemotherapy and radiation therapy—don’t seem as daunting and are better tolerated,” Zureikat says.

“We recently performed a multi-institutional comparison of open and robotic Whipples at eight large hospitals within the U.S., including UPMC, and found the robotic Whipple to be associated with fewer complications compared to the open approach,” he adds.

Whichever way you have Whipple surgery, a hospital stay is required. Recovery time depends on physical condition before surgery and the complexity of the operation, but most people are able to return to their usual activities four to six weeks after surgery.