Personalizing Pancreatic Cancer Treatment

Linda Bartlett; National Cancer Institute

The genetics of circulating tumor cells provides therapeutic clues.

For decades, pancreatic cancer has managed to stymie scientists searching for new drugs and new drug combinations that can halt the progression of the disease. One scientist taking on that challenge is Dr. Mark Ricigliano, a researcher who has devoted much of his career to developing and designing diagnostic tests to personalize chemotherapy treatments for pancreatic cancer patients.

The research falls under the umbrella term “pharmacogenomics.” What that means is that scientists study how specific genes—those short segments of DNA that tell your cells how to function and what traits to express, like straight or curly hair, for example—affect an individual’s specific response to medications. The hope, of course, is to develop treatments that are geared to an individual’s tumor genetic makeup.

It’s a huge challenge, but one that Ricigliano knows is necessary.

“Patients with pancreatic cancer are hoping for some type of breakthrough that can not only make current treatments more effective, but also technologies that can provide information as to whether a treatment is actually working for them,” says Ricigliano, founder and director of Germantown, MD-based Adera BioOncology, which develops assays and companion diagnostics for pancreatic cancer. “It’s rewarding to work on research that can ultimately go from our lab to these patients and, hopefully, positively affect them.”

Ricigliano’s work is focused on so-called circulating tumor cells, basically rogue cells that break away from a primary tumor, enter the blood stream and eventually invade other organs. Once this process of metastasis begins, treatment becomes much more difficult.

Tumor Genetics Predict the Best Approach to Treatment

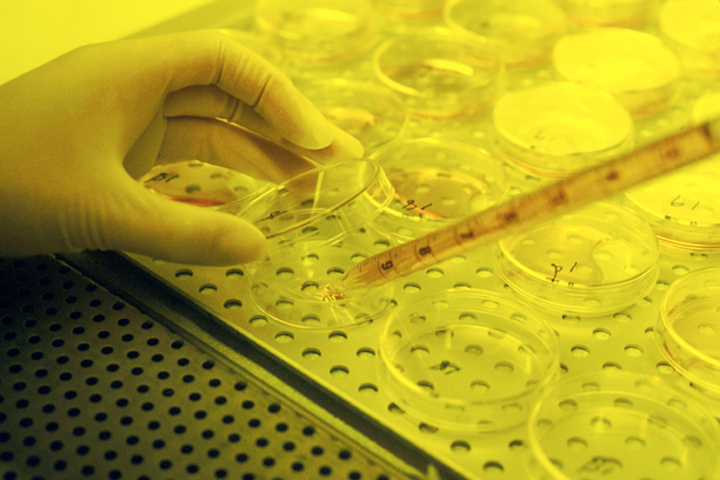

In his lab, Ricigliano maps, or profiles, specific genes being expressed by these circulating tumor cells. And with the profile they may be able to help doctors predict whether a patient with pancreatic cancer is responding to treatment well before that patient would receive a CT scan to determine the treatment’s effectiveness. The tests may also be able to determine what specific regimen may be better for a patient, and if that patient is becoming resistant to a current regimen.

“Patients always ask why do I have to wait for a scan to see if treatment is working, why can’t my doctor tell me now?” says Ricigliano, adding that he receives about 200 patient samples a year from across the U.S. and Europe. The samples are from participants in investigational studies he and colleagues are conducting.

So far, Ricigliano has found seven pancreatic cancer biomarkers that can be evaluated in his lab. “All a patient needs to do is to have a blood sample taken,” he explains, adding that biomarkers are simply genes in the cancer cell and the expression or mutation of these genes may provide biological information to doctors.

“Each biomarker can provide us different information,” explains Ricigliano. “It’s actually incredible and very powerful.”

For example, one biomarker gene called ALDH1A1 provides information on the extent of pancreatic circulating tumor cells. When the expression of this gene is elevated it could signal active metastatic disease. Another biomarker called BCRP is a multi-drug resistance gene. If there are elevated levels of BCRP it can be associated with drug resistance.

While a blood test is a relatively easy process for the patient, the evaluation of these biomarkers relies on highly sophisticated computer modeling programs to determine potential treatment options, to see if the disease has progressed, or to figure out if a person is responding to treatment.

Finding Answers With Investigational Trials

One question plaguing doctors treating cancer is why some rare people seem to respond to certain types of treatment, mainly chemotherapy, that do not seem effective for other people. These “extraordinary responders” are also a focus of Ricigliano’s current clinical trial in pancreatic cancer. “What we want to do is find out what makes these people so unique, what is it about their genomic profile that makes them so responsive,” he explains.

He and colleagues from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York; UCLA; University of Nebraska; Weill Medical College of Cornell University in New York; Maastricht University Medical Center in the Netherlands, and Hematology and Oncology Specialists in Denville, NJ, are involved in an observational study enrolling patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer to help identify those genomic differences between exceptional responders and non-responders to standard of care chemotherapy. Data analysis of the gene expression profile of the exceptional responders compared to non-responders will define those genomic patterns that may help understand their response to chemotherapy, says Ricigliano.

He is also the recipient of a $4 million joint NIH grant with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to fund a clinical trial to validate a test that will help doctors choose between FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine–nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane)—two first-line chemotherapy treatments for advanced pancreatic cancer. Funds from the grant will also be used to improve methods for culturing and growing of circulating tumor cells into organoids—essentially a three-dimensional hollow sphere of cells that contains that patient’s genomic profile. “I can grow the cells now to 21 days, but the hard part will be passaging the cells to full organoids,” says Ricigliano, adding that work will be done at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island.

Early Adopters Make a Difference

None of the research being done could come to fruition without the expertise of “early adopters,” doctors, other medical professionals and, of course, patients who are willing to try new therapies and treatment approaches as soon as they are available.

“These early adopters don’t accept the status quo,” says Ricigliano. “Their focus is to try the latest that science can offer, and it’s from them that we learn how to ultimately make the biggest difference in the lives of those with pancreatic cancer.”

Ricigliano is hopeful about the future of pancreatic cancer treatment. “We’ve come a remarkably long way in the last few years and, yes we have a long way to go yet, but it’s a very exciting time,” he says. “The focus is always the patient. These people want answers and new treatments and I am confident we will find a better way to help them. It will be a process, but we are getting there.”