mRNA Vaccine Shows Promising Results

Proteins are large, intricate molecules that do most of the work in our cells.

Although most of us have heard of proteins and cells, most of us never heard too much about mRNA outside of a high school biology class. But it’s mRNA, which stands for messenger ribonucleic acid, that tells our cells which proteins to make so that bodily functions like tissue growth and maintenance, fluid balance, immune function, and more all happen seamlessly.

After the incredible success of mRNA-based vaccines in helping to curb hospitalizations and deaths from COVID, mRNA is now center stage. But mRNA technology isn’t new; it’s actually been more than four decades since scientists attempted to transport mRNA into mouse and human cells to induce protein expression. The idea behind an mRNA vaccine is that scientists could potentially tell our cells to make proteins to better recognize an invader.

mRNA Vaccine and Pancreatic Cancer

A new vaccine developed using the same technology as the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID vaccine is raising some intriguing possibilities in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. In an initial trial, half of the pancreatic cancer patients receiving the vaccine remained cancer-free 18 months later.

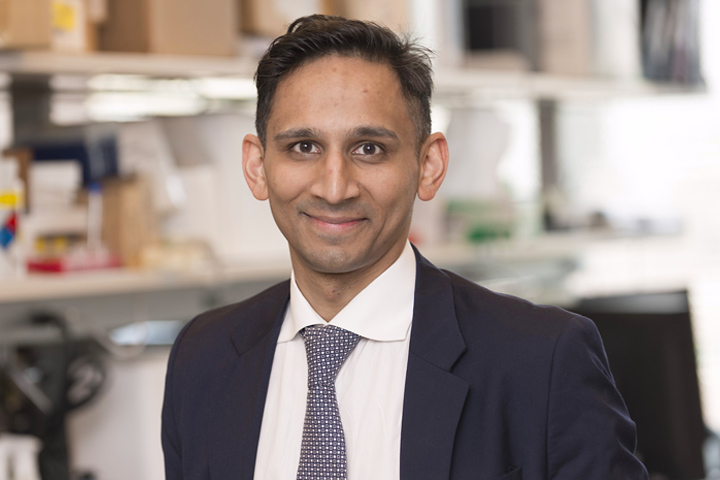

The treatment was developed by surgeon–scientist Vinod Balachandran, M.D., of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York City, working together with the biopharmaceutical firm BioNTech and the biotechnology company Genentech. The results of the trial were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2022 conference.

“I think it’s really exciting for pancreatic cancer. We need urgent progress in treating this disease,” says Balachandran. “Though surgery remains the only potential chance for a cure, far too many patients have recurrences despite surgery and chemotherapies.”

The Long-Term Survivor Connection

The hypothesis for the study goes back to initial work in Balachandran’s lab, where researchers were trying to find an answer to a perplexing question: What is it about long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer that makes them different? And can that difference be exploited into potential drugs or therapies for other pancreatic cancer patients? What the researchers found is that one of the striking differences between the so-called exceptional responders to pancreatic cancer treatment and those that don’t fare as well is the presence of molecules called neoantigens in their tumors that are recognized by immune cells called T cells.

In papers published in November 2017 and May 2022 in the journal Nature, Balachandran and his colleagues reported that long-term pancreatic cancer survivors have tumors that are especially immunogenic, meaning their tumors are spontaneously recognized and attacked by T cells. In these patients, neoantigen-specific T cells were found patrolling the body even a decade or more after treatment. The researchers concluded that the T cells may have been keeping the cancer from returning.

Significantly, the team also found neoantigens in the tumors of people who were not long-term survivors. Although these neoantigens were not spontaneously recognized by T cells, their presence suggested that vaccines incorporating the right neoantigens might spur the immune cells into action—bringing the same anticancer effect.

“It was a striking finding,” Balachandran explains. “The evidence suggested that at least one of the distinguishing features of these long-term survivors and their exceptional outcomes was the ability of these patients’ immune systems to spontaneously recognize neoantigens in their tumors.”

“We thought if long-term survivors reflected the best-case scenario when your immune system spontaneously recognizes neoantigens, could we replicate this scenario in other patients by boosting the immune system with a vaccine?”

Based on this finding, Balachandran and MSKCC colleagues launched a clinical trial in 2019 to test a vaccine using mRNA in people with pancreatic cancer. In this case, each pancreatic cancer vaccine is personalized for the individual patient and contains neoantigens from their tumors most likely to stimulate T cells.

This clinical trial, the first to use mRNA to treat pancreatic cancer, was completed a year ahead of schedule in 2021, despite having to conduct the trial in the middle of a global pandemic.

About the Study

The investigator-initiated, single-site, phase I trial was designed to evaluate the treatment of an individualized immunotherapy called autogene cevumeran in combination with an anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor atezolizumab. Anti-PD-L1 agents are another form of immunotherapy. This regimen was an add-on to the standard-of-care regimen with adjuvant chemotherapy mFOLFIRINOX in patients with resected pancreatic cancers. The primary objective of the study was to assess the safety of this regimen. Secondary objectives include the efficacy of the treatment, as measured by 18-month relapse-free survival. The researchers also wanted to gauge immunogenicity as well as the feasibility of the treatment regimen.

In eight of 16 patients studied, the vaccines activated T cells that recognized the patient’s own pancreatic cancer. These patients also showed delayed recurrence of their pancreatic cancer, suggesting the T cells activated by the vaccines may be having the desired effect to keep pancreatic cancer in check.

“Pancreatic cancer is just so deadly. It resists all current treatments, including immunotherapies,” Balachandran notes. “We used to think pancreatic cancers did not have enough neoantigens for such vaccines. These results show that we can leverage mRNA to teach the immune system of pancreatic cancer patients to recognize neoantigens, and therefore their own tumors.”

The next step, he says, is a larger, randomized trial. “This will give us more important information on how to best treat pancreatic cancer patients with these exciting new therapies,” says Balachandran.