Most Cancer Mutations Are Random DNA Mistakes

Random, unpredictable DNA “mistakes” account for nearly two-thirds of the mutations in cancers, according to a new study published in the March 24 edition of the journal Science earlier this year.

In the study, Johns Hopkins researchers placed these cancer-causing mutations into one of three categories. The study included 32 different types of cancer.

Although some mutations may be more powerful than others, the scientists concluded that 66 percent of cancer-promoting mutations arise randomly during cell division in various organs throughout a person’s life. Another 29 percent can be due to environmental causes, and 5 percent are inherited.

The researchers also agree—in keeping with most epidemiologic studies—that about 40 percent of cancers are preventable. That, they say, points to the fact that significantly more research into early detection strategies is vital.

What About Pancreatic Cancer?

Pancreatic cancer was indeed included in the study and the researchers concluded that 5 percent of mutations were inherited, 32 percent were environmental and 63 percent were random.

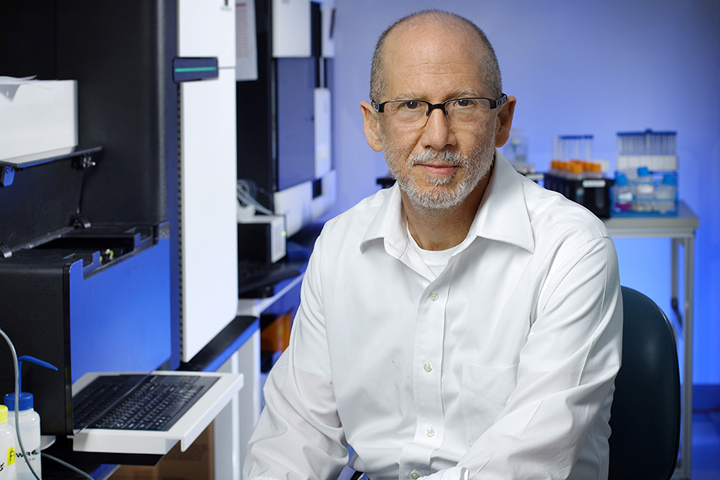

The realization that there are three different causes for the mutations underlying pancreatic cancer has important implications for patients, says study co-author Bert Vogelstein, M.D., co-director of the Ludwig Center at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, Baltimore, Maryland.

For example, if an individual has a family history of pancreatic cancer, it is essential to consult with an expert in genetic counseling, he says. “Patients at risk for pancreatic cancer are often at risk for other types of cancer, depending on the nature of the mutation they inherited from their parent,” Vogelstein explains. “Screening is available for some of these cancers, such as breast cancer, and if caught early, such cancers can be cured simply by surgery. Some cases of hereditary pancreatic cancer can also be caught at early stages if they cause cysts, for example, and surgery for these can be curative.”

Random Mutations = Bad Luck

It is well-accepted that the environment, particularly those associated with certain lifestyles, contributes to pancreatic cancer. For example, smoking and obesity have been shown to substantially increase the risk for contracting pancreatic cancer as well as many other cancer types. Individuals that do not smoke (or quit smoking), exercise regularly, and eat healthy diets are less likely to develop cancer and more likely to live longer, healthier lives.

“But many pancreatic cancers occur even in individuals who lead exemplary lifestyles and have no hereditary risk factors,” Vogelstein says. “These individuals are the victims of bad luck, mistakes that cells make when they replicate their DNA.”

In most cases, these mistakes cause no damage, but that is not true in the case of patients who develop pancreatic cancer. “It is important that pancreatic cancer patients who studiously avoided risky lifestyles do not feel guilty and do not wonder why they developed pancreatic cancer,” Vogelstein says. “There is nothing they could have done to avoid it, and we now understand why such cancers can develop even in people in perfect environments.”

A Need for Earlier Detection

Vogelstein would like to see more research on early detection, and eventually ways to spot early-stage pancreatic cancer, when it is still potentially curable by surgery. Plus, all treatments for every cancer work better when patients are treated earlier, when they have less disease, he says, adding that earlier detection, combined with better therapeutics, is the key to reducing deaths from pancreatic cancer.

As longevity increases, aging alone gives rise to more random copying errors, which is why pancreatic cancer occurs more frequently in older individuals. But as the population ages, and hopefully environmental risk factors are reduced, the number of cancers that are strictly due to bad luck will increase, making the development of better methods of early detection even more important.

“A healthy centenarian whose pancreatic cancer is diagnosed at a very early stage can still be cured by surgery, particularly with the advanced surgical techniques that will be developed by the time that centenarians represent a large population group,” Vogelstein says.

Funding for the research was provided by the John Templeton Foundation, the Lustgarten Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research, the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the Sol Goldman Pancreatic Cancer Research Center, and the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute.