Before You Leap: Genetic Testing for Pancreatic Cancer

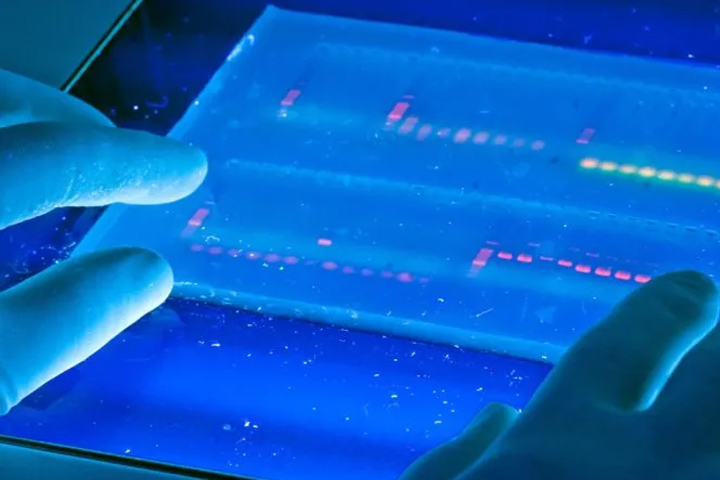

University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability; Flickr

Your father had it. Your aunt had it. And rumor has it that some cousin was afflicted.

If other family members had pancreatic cancer, what are the chances you will get it too? Are they any higher than the 1 in 65 lifetime risk that everyone faces? Is there a test to tell?

Familial pancreatic cancer is a thing—between 5 to 10 percent of cases can be pinned to a hereditary condition. Others have an unidentified source but occur in families with a strong history of the disease. There are tests to tell, but they are not one-size-fits-all.

Scientists have been able to trace pancreatic cancer to mutations in a variety of genes that may predispose patients to the disease. These include genes linked to disorders that can lead to cancer, such as Lynch syndrome (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (STK11), Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer syndrome (BRCA1 and BRCA2), and Familial Adenomatous Polyposis, or FAP (APC).

Because of the range of mutations, genetic testing to assess pancreatic cancer risk has been equally wide in scope. Before the advent of multiple gene “panels,” testing had to be focused on one gene at a time. It is now possible to test several genes at once, but targeted testing is still important in order to get the most accurate and informative results. Efforts are currently underway at New York University’s Pancreatic Cancer Center to create a simple blood test and a tablet-based electronic survey to assess potential risk. (To learn more about this effort read “Pancreatic Cancer and Family History.”)

In the meantime, it’s best to seek out a genetic counselor or doctor who is knowledgeable about genetic testing. They will start with a detailed family history, to determine things like the types of cancers, the age at which they occurred, whether they appeared in many generations, or more than once in each individual. Familial pancreatic cancer is defined as having at least two first-degree relatives diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Armed with your familial health history, genetic counselors can then recommend certain tests based on their extensive knowledge of known genetic links. These tests are ideally started on a family member who has had a cancer diagnosis.

There are many labs that offer testing, but not of the over-the-counter consumer variety. Doctors or genetic counselors can order the test most applicable to your specific genetic risks, from labs they trust.

Reading Results

The tests themselves are straightforward—usually a simple blood draw or saliva swab—but the results may not be. For instance, there are “variants of uncertain significance” (VUS), meaning scientists aren’t entirely sure what it means based on the information at hand. Megan Frone, M.S., CGC, a genetic counselor at the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, says VUSs, as they are called, are not uncommon.

“As we gather more information about a particular VUS over time, many (but not all) end up being reclassified to benign variants. But the uncertainty can be frustrating for patients and clinicians alike,” she explains. If the test comes back negative, that’s not necessarily the end of the story either. Some tests don’t find an underlying cause of a hereditary cancer, but the family history still suggests one. “There could still be residual risks that should be taken into account when considering future health decisions,” Frone notes.

Taking Action

Those at elevated risk could be good candidates for screening. Screening options for pancreatic cancer include: endoscopic ultrasound, in which a thin, flexible tube is passed through the mouth into the first part of the small intestine near the pancreas to capture an image and biopsy if needed; and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which works similarly to a standard MRI scan to take images of the pancreas.

These tests are aimed at detecting precancerous or early cancerous changes in the pancreas, in hopes of diagnosing the cancer at an early, more treatable stage. Those found to have mutations in specific cancer predisposition genes linked to other cancers may also want to undergo additional screening for those cancers.

And all should consider lifestyle changes, such as maintaining a healthy weight and getting enough physical activity. Smoking has also been linked with pancreatic cancer, often at an earlier age.

Look Before You Leap

Frone, who has coached hundreds of adult and pediatric cancer patients and their families through the genetic testing process, says she likes to prime patients in advance. “These tests have huge implications for patients and their families. Really thinking through what it will mean for them and their loved ones is so important, and it’s something I like to address both before and after the test is taken,” Frone states.

Some of the questions Frone encourages potential test-takers to consider:

- What will you do with this information?

- What will the results mean for you? For your family members?

- Do you have any concerns—such as potential for insurance discrimination—that you would like to address before you undergo genetic testing?

It’s also important to remember that cancer is a common disease—nearly one in two men and more than one in three women in the US will develop cancer during their lifetime—so it’s no surprise that many families have at least a few members who have had it. It may be because they share certain behaviors or exposures that increase cancer risk, such as smoking or obesity. Even in cancer that is inherited, what is inherited is the non-functioning gene that can increase the risks for certain cancers, and not the cancer itself.

Because of the complexity of genetic testing and its implications, Frone strongly recommends that anyone considering it consult either a genetic counselor or clinician with expertise in the process. The National Society of Genetic Counselors has a list of providers on their site who can provide services both in person and remotely.

To learn more about specific genetic mutations read “The ABCs of Genetic Testing.“

Tumor Registries Aid Research

Besides genetic testing, if you have a family history of pancreatic cancer you might consider joining a family tumor registry. There are 17 of these registries in the U.S. and Canada. Scientists at the Sol Goldman Pancreatic Cancer Research Center’s National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry collect information about families with more than one member who has been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Nearly 5,000 families have enrolled so far. Participation involves the completion of a health history questionnaire and, in some cases, a donation of a DNA sample. The data is entered into a computer program that creates a family pedigree, and helps researchers better understand how and why pancreatic cancer clusters in some families.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s registry is profiled in “A Registry for Those at Risk for Pancreatic Cancer.” For information about the other registries, visit the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network Family Registries page.