Understanding a Family’s Risk for Pancreatic Cancer

With inherited genetic changes probably playing a role in most pancreatic cancers, researchers are keen to identify people at risk for the disease.

One huge step in helping to identify those individuals and families is through research geared not only to identifying those genetic changes that place people at higher risk. Equally important is research to help develop ways in which doctors can more readily identify those people who may be carriers of those genetic changes.

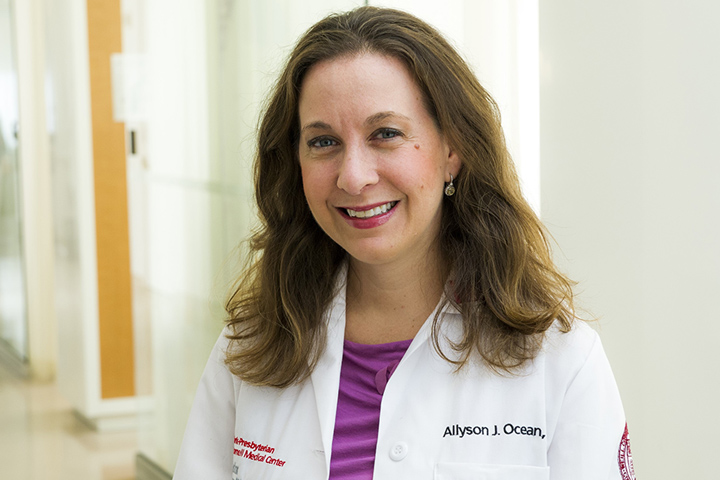

The first step: patient and family registries like the National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry at Johns Hopkins (NFPTR.) The Johns Hopkins registry is a research-based endeavor and has been active for more than 20 years, explains Alison Klein, Ph.D., NFPTR director. “What we have been able to show is that pancreatic cancer does run or cluster in families and that there is likely to be a genetic cause to this clustering,” says Klein. “Pancreatic cancer, as we all know, has a very poor prognosis, so by studying families enrolled in our registry, we hope to find some answers as to how we can improve outcomes for patients like they have in other cancers.”

Currently, the registry has enrolled about 4,000 families. In some cases, families have more than one close relative who has been diagnosed with the disease. In others, only a single member of a family has been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. All participants are vital to gaining a better understanding of the disease and developing not only early detection programs, but perhaps personalized treatment plans.

Genetics Helps Find Answers

The Johns Hopkins registry has already been able to identify several familial pancreatic cancer susceptibility genes. And they were among the first to conduct early detection screening trials.

Among other findings, the group has also shown that individuals who have a strong family history of pancreatic cancer have a nine-fold increase in the odds of developing the disease during their lifetimes.

“What we are doing is in one sense providing a frame for genetic counseling and screening,” says Klein, adding that the group developed a tool called PancPRO to help determine risk. “We know how genes behave, and coupled with information about a family—who has the disease, their age, family size, and causes of death—our model can provide a good estimate of an individual’s risk,” she adds.

Possible Genetic Culprits

Researchers do know that about 10 percent of pancreatic cancers are caused by inherited genes. But DNA is not necessarily destiny, explains Klein. Essentially, if there is a 100 percent certainty that an individual carries a pancreatic cancer gene, that individual’s risk of being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer during their lifetime is only about 25 percent.

Although researchers have identified some of the genes responsible for so-called family clusters of the disease, the majority of the genes, more than 80 percent, have not yet been identified. Some of the genes that have been linked to familial pancreatic cancer may sound familiar, specifically BRCA2, the so-called breast cancer gene. Researchers at Johns Hopkins, and other teams, have shown that up to about 12 percent of familiar pancreatic cancers are linked to an inherited defect in this gene. The Johns Hopkins team is also studying patient-specific populations, like those of the Ashkenazi Jews and African-Americans.

Among African-Americans, who have high incidences of the disease and among the poorest prognoses, early studies suggest that socioeconomic factors and environmental factors, such as cigarette smoking, may play a role. The population also has higher incidences of pancreatitis and diabetes, which have already been linked to the development of pancreatic cancer.

Ashkenazi Jewish families are also of vital importance to the team’s research efforts. “The incidence of pancreatic cancer in this population is also very high, and we don’t know yet if due to inheritance or the environment, for example, but by studying the family history, we may be able to find out,” says Klein.

A Look to the Future

Going forward, the registry’s research work will involve identification of those genes that place people at higher than average risk, and the development of ways to use those genetic discoveries and early detection biomarkers to provide a means of early detection of pancreatic cancer. It’s a tall order, but one that Klein believes is ultimately possible.

“I think one of the most important things we can do as researchers is to let the public know that progress is being made in pancreatic cancer,” she says. “We need to raise awareness of pancreatic cancer, and potentially have more patients and families involved in our research. The potential for diagnosing pancreatic cancer in its early stages, along with the tremendous work that’s being done on the treatment end, can be a very important difference as we try to beat this disease.”

To learn more, and to see if you and your family may be eligible to participate in this research, please visit the National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry at Johns Hopkins.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center also has a Pancreatic Tumor Registry. Learn more about it by reading the story “A Tumor Registry for Those at Risk for Pancreatic Cancer.”