Laboratory Study Shows Keto Diet May Enhance Chemotherapy

Keto is having a moment.

The keto diet is a fatty food lover’s dream, with celebrity endorsements and copious amounts of social media chatter extolling its virtues as everything from a weight loss miracle to a recipe for living longer.

One theme in cancer biological research is also having a moment. Scientists are trying to uncover the underpinnings of how metabolic regulation is intrinsically linked to cancer progression. After all, the viability of cancer cells—actually, all cells—is regulated by the supply of various nutrients. Take away those nutrients and a cancer cell would presumably die.

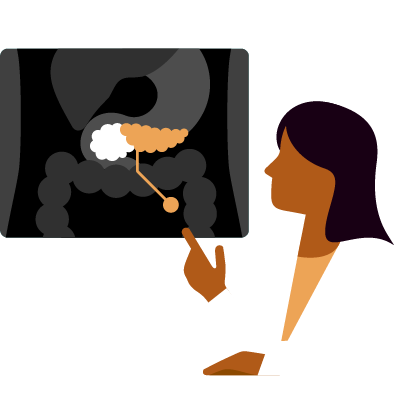

In a preclinical study published in the journal Med, researchers examined the effect on pancreatic tumor progression when a specially formulated keto diet was combined with a triple-cocktail chemotherapeutic regimen. Now, the results of that study are being translated into clinical research.

Keto Plus Chemotherapy Extends Survival Time in Mice

The preclinical study, led by Joshua Rabinowitz, M.D., Ph.D., showed the keto diet alone had absolutely no effect on tumor growth. But when it was combined with chemotherapy, survival time was tripled compared to chemotherapy alone. “It was really an exciting result to me. The first time we ran the experiment it worked particularly well, and I was immediately focused on replicating it. The good news is that the result is quite robust in mice,” says Rabinowitz, the Ludwig Cancer Research Princeton Branch Director, who also serves as a professor in the Department of Chemistry and the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey.

But mice are not humans, “which is why it’s very important this work is being translated to a human study,” Rabinowitz explains. The chemotherapeutic regimen used was nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and cisplatin—standard chemotherapies for advanced pancreatic cancer. Notably, while the therapeutic benefit did not depend on the immune system, only mice with intact immune systems were among the long-term survivors.

“We’ve seen progress in pancreatic cancer, but it’s just not enough,” says Rabinowitz, who lost a great uncle and a very close friend to the disease. “Most of the time pancreatic cancer is diagnosed in an advanced stage. And although chemotherapeutic regimens have improved in stabilizing or shrinking tumors, the benefits to a patient don’t last long. We don’t often see three-plus years of survival that people would, at a minimum, hope for. So we clearly just need to find ways to improve on what we have now.”

Years of Research

In the current published study, Rabinowitz and his colleagues conducted numerous experiments over the course of several years. Their patients: mice that were engineered to develop pancreatic cancer or that were implanted with tumors similar to those found in pancreatic cancer patients. The mice were fed either a normal, carbohydrate-rich diet or a specially formulated ketogenic diet, and then were treated with the standard-of-care chemotherapy combination of nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and cisplatin.

Rabinowitz and his team also conducted studies to explore the effects of the combination therapy on tumor metabolism. Glucose is a major energy source for cancerous cells. Insulin is a cancer-promoting hormone. A ketogenic diet deprives the body of carbohydrates, which, in turn, dramatically lowers the amount of glucose and insulin available to cells. In this study, the researchers found that the keto diet decreased the levels of glucose in the malignant tumor more than it did in healthy tissues, while also profoundly suppressing insulin levels.

One of the known aspects of the keto diet is that the body is deprived of sugar or glucose, so the body in turn breaks down fats and generates ketones that cells burn through to generate energy to survive. One such ketone is 3-hydroxybutyrate—a small fuel substrate that can substitute for and alternate with glucose under conditions of fuel and food deficiency.

“In a sense it’s like a supercharged fuel that dumps electrons into cells,” Rabinowitz explains. “Malignant cells are very good at taking it up, but when cancerous cells take up too much of this fuel it may be toxic to those cells.” That toxicity has to do with the proliferation of unstable molecules called reactive oxygen species that are also generated by chemotherapy. The researchers believe this may enhance the antitumor effects of the chemotherapy.

“The chemotherapy regimen we used is what’s used in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer,” says Rabinowitz. “So we know that for some patients it works. It’s active in shrinking tumors and slowing progression. The preclinical work we did was actually very rigorous. Those mice that were on keto and had chemotherapy did amazingly well. I hope that we can see the same thing in patients.”

There is a caveat. “The translation from mice to humans is very perilous,” adds Rabinowitz. “Our mice were on a particular type of keto, and we need to mimic that as best as possible in the trial. But if this proves beneficial it could be another material benefit to chemotherapy that can bring a meaningful positive change to pancreatic cancer patients who have to contend with a heart-wrenchingly difficult diagnosis.”

To Learn More

Based on this and other research, a randomized, phase II trial has been developed. It is designed to evaluate the progression-free survival in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer on triplet therapy (nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, cisplatin) while on a ketogenic diet or a non-ketogenic diet. This study also aims to compare the changes in serum metabolites and quality of life between the two arms. The dietary aspects of the study are being carefully monitored.