An Immunotherapy Game Changer

Genetic research is giving scientists a better understanding of the origins of cancer.

From that information, the hope has always been to find a cancer treatment based on specific molecular changes that allow abnormal cells to replicate no matter if the cells were found in the pancreas, the breast or the lung. It seemed like the stuff of science fiction.

But in May, for the first time in its history, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave accelerated approval to an immunotherapy drug called pembrolizumab (Keytruda, manufactured by Merck) for the treatment of any type of advanced pediatric or adult cancer based strictly on its genetic profile—not its location.

The drug, which first gained widespread attention after former President Jimmy Carter was treated with it during his battle with melanoma, is now approved for use for any solid tumor carrying a genetic flaw called a mismatch repair defect. For this subset of patients, that genetic glitch makes tumors more susceptible to immunotherapy. Although this flaw is found most often in patients with colorectal, endometrial, and gastrointestinal cancers, it can also be present in other types, such as bladder, thyroid, and pancreatic cancers, among others.

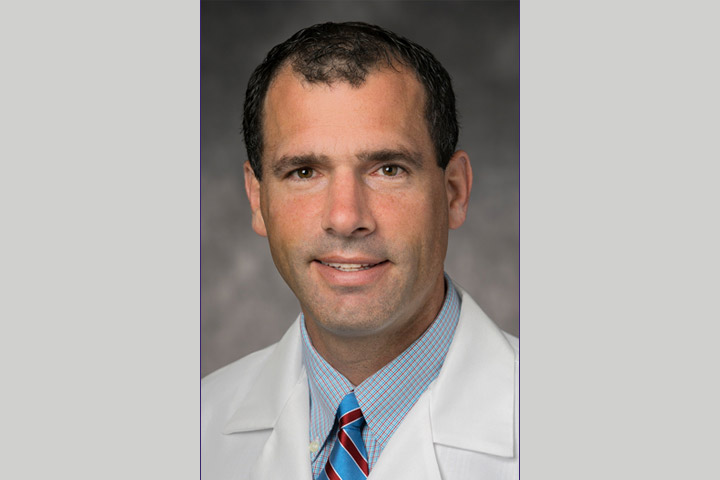

For pancreatic cancer patients with advanced disease who have a mismatch repair defect in their tumors, this drug could be a “game changer,” explains Dr. Luis Diaz, who was the principal investigator on the pivotal trial that spurred the FDA’s landmark approval. He led the trial when he was an associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins (Baltimore, Maryland) and he now heads the Division of Solid Tumor Oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York). The trial was funded through philanthropic efforts of numerous organizations including the Lustgarten Foundation, and Swim Across America, among others.

“Pancreatic cancer is a lethal scenario that may be turning into a more manageable one for certain patients, and that’s just incredible,” he says. “It’s exciting to have been part of that work, but I’m just absolutely thrilled for patients who may benefit.”

What Is Mismatch Repair?

Immunotherapy works on the principle that a patient’s immune system will recognize cancer cells as foreign and then mount an attack to destroy them. But cancer tumors are smart and set up their own defense against the immune system. One way is by cloaking proteins on their surface. That makes cancer cells invisible to the immune system. Pembrolizumab rips off the cloak, making cancer cells visible. But it doesn’t work for everyone.

One answer as to why came after a study in which one colon cancer patient responded remarkably well to Keytruda, while others did not. “We wanted to know why this individual responded so well, and after asking the right people the right questions, and doing the right tests, we found out that patient had a mismatch repair defect,” says Diaz, “And that got the ball rolling for other studies.”

Very simply, a mismatch repair defect means that DNA can’t repair itself when there is an error, or mutation.

Some tumors, like those in lung cancer, have many mutations, mostly due to cigarette smoke. The same is true for melanoma and exposure to sunlight. That’s why drugs like Keytruda may work well for them. “Essentially, the more mutations, the better chance of those mutations being recognized as an invader,” explains Diaz.

But other types of tumors don’t have many mutations, unless that tumor has a mismatch-repair deficiency. “To put it in perspective, an average cancer cell has about 70 mutations while an MMR-deficient cell has about 1,700, and that provides a huge target for the drug,” Diaz says. Some estimates show that mismatch repair defects may occur in about five percent of patients with 11 different types of cancer.

“That doesn’t sound very big, but that’s a huge number of cancer patients who can be potentially helped,” Diaz states, including about 3 percent of pancreatic cancer patients who may carry the defect.

Remarkable Data

The study, published in the journal Science, recruited 86 participants, representing 12 different types of cancer. All tested positive for mismatch repair defects and had failed to respond to at least one prior therapy. They received pembrolizumab intravenously every two weeks for up to two years.

Slightly more than half of these participants (46) had an objective response—their tumors shrank. Of these patients, 18 patients had a complete response. That means the cancer vanished. In all, 66 of 86 (77 percent) had at least some degree of disease control, including those who had partial responses, meaning their cancers shrunk by at least 30 percent in diameter, and complete responses, meaning no radiologic evidence of the tumor. This also included those whose tumors did not grow, but remained stable. At one year after the start of therapy, 65 of the 86 patients (76 percent) were alive, and 55 of the 86 (64 percent) were alive at two years.

“Durable responses like the ones we observed are rare, and I’m not going to lie, we were just astounded,” Diaz says. “Some of these patients were so very sick.”

Get Your Tumor Tested

Based on the trial results and its approval by the FDA for any tumors carrying the mismatch-repair defect, Diaz and others encourage pancreatic cancer patients—and all others—to get tested to determine the tumor’s molecular profile. Tests are commercially available.

“I can’t stress enough to just get tested,” Diaz says. “This will not help everyone with advanced pancreatic cancer, but it may help some. But this is another tool in our toolkit, so we need to take advantage of it.”

“It will give some people who are out of options another chance.”