Gut Reaction for Pancreatic Cancer

When you hear the word “microbiome,” think of a community.

That’s because a microbiome is a community made up of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microscopic living things that are collectively referred to as microbes. Humans have a robust microbiome made up of trillions of these tiny organisms. So do plants, as well as our pets. Malignant tumors also have microbiomes, and scientists are looking at the pancreatic cancer microbiome to better understand what makes this too-often lethal disease tick.

In the lab of physician–scientist Florencia McAllister, M.D., at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Texas), she and her team of researchers have a lofty goal: bringing cancer early detection, immunoprevention, and immunotherapies from the lab bench to the bedside. With a special interest in gastrointestinal cancers, particularly pancreatic cancer, the team is focusing its efforts on gaining a better understanding of the role of the immune system in immunosurveillance and immunoevasion. It’s these processes by which cells of the immune system look for and recognize foreign invaders like bacteria and cancerous cells, and how these cancerous cells elude the army of immune cells whose job is to protect the body from these pathogens.

McAllister and her colleagues are also studying the basic mechanisms that regulate the immune system’s responses to tumor initiation—that point in time when normal cells are changed so that they are able to form tumors—and tumor progression, or how a tumor grows and spreads. And they want to learn more about how bacteria found in the tumor microbiome may affect the body’s immune responses to cancer.

“What excites me [about bacteria and the microbiome] is that we know so little, but what we are finding is so promising,” says McAllister, who is an Associate Professor in the Department of Clinical Cancer Prevention and the Department of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology. “We’re specifically interested in understanding the mechanisms that bacteria use that affect immune activation, for example. We are just scratching at the surface of this. But there is so much that can be done in this area from a basic perspective that could forge a novel angle to future therapies.”

Pivotal Study Paves the Way

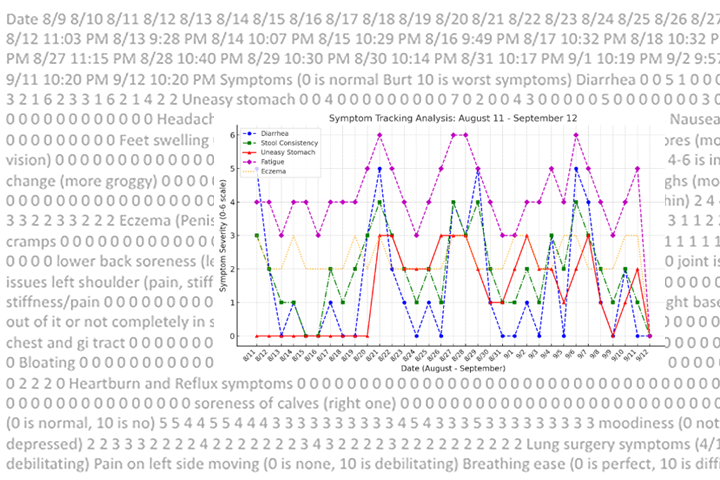

In 2019, McAllister and her team in conjunction with a team at Johns Hopkins showed that the tumor microbiome is different when comparing those individuals with pancreatic cancer who have longer-term survival versus those with shorter-term survival. Indeed, researchers don’t know why some people with pancreatic cancer defy the odds and survive longer, but some scientists suspect this could be due to the immune system and how the tumor microbiome affects that system.

The researchers found that the microbiomes of long-term pancreatic cancer survivors were actually more diverse and had a specific bacterial signature. The long-term survivor cohort had undergone surgery and then survived on average 10.1 years after surgery, while the short-term survivors died within five years of surgery, with survival averaging just 1.6 years.

Those long-term survivors had higher numbers of microbial species within their tumors as well as a higher relative abundance of a group of microbes. These results were independent of factors that may have affected the tumor microbiome, such as prior treatment, body mass index, or antibiotic use.

Further research showed that tumors of long-term survivors also tended to have much higher numbers of cell-killing T cells than tumors in short-term survivors, and there was bacterial migration from the gut to the tumor.

From these findings, the team then transplanted stool samples from human long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer into a mouse model of the disease, which resulted in changes to the animals’ tumor immune responses and microbiomes and ultimately reduced pancreatic cancer growth.

An Antibiotic Connection

Once the team found that pancreatic cancer was associated with these microbes, and changes to those microbes affect tumor growth, they began exploring other avenues. “We started to think about antibiotics,” explains McAllister. “Previous reports have described that bacteria secrete an enzyme that can alter the metabolism of gemcitabine, which is commonly used in pancreatic cancer treatment. And in mice models, antibiotics can also delay pancreatic cancer growth.”

In a retrospective study, Dr. Chirayu Mohindroo, and Dr. Merve Hasanov (part of the McAllister Lab team at the time and now both internal medicine residents) looked at clinical data of patients with resectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer seen at MD Anderson Cancer Center from 2003 to 2017. Included in their analysis was information regarding demographics, chemotherapy regimen, and antibiotic use, including duration, type, and reason for indication.

A total of 580 patients with pancreatic cancer were included, 342 of whom underwent surgery and 238 who had metastatic disease. Antibiotic use for longer than 48 hours was detected in 209 resected patients, or 61 percent, and 195 metastatic patients, or 62 percent. Among resected patients, the team did not find differences in overall survival or progression-free survival based on antibiotic intake. However, in the metastatic cohort, antibiotic consumption was associated with a significantly longer overall survival of 13.3 months versus 9.0 months, and progression-free survival of 4.4 months versus 2.0 months.

When the team analyzed the groups by chemotherapy regimen, they found that the 118 patients who received gemcitabine-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy had significantly prolonged overall survival and progression-free survival if they received antibiotics, while the 98 patients receiving 5-FU-based chemotherapy had only prolonged progression-free survival.

Complex Questions Require Out-of-the-Box Thinking

Although these studies are early stage and larger trials are needed to validate findings, McAllister and her team are hopeful. “It’s exciting that we are linking microbes to cancer progression and therapies responses, but we have to remember these are very early days, and what we do not know about microbes in cancer is much more than what we know,” says McAllister.

“These are all very complex questions, and clearly larger trials need to be done. But I am excited about this because I do believe that we and other labs are absolutely on to something regarding bacteria and immune responses.

“Pancreatic cancer is just a terrible disease. My mom died from it, and myself and others are absolutely committed to finding ways to improve treatment for the disease. But to get there we can’t keep repeating the same concepts, and we all need to be thinking out of the box.”