BRCA’s Role in Pancreatic Cancer Investigated

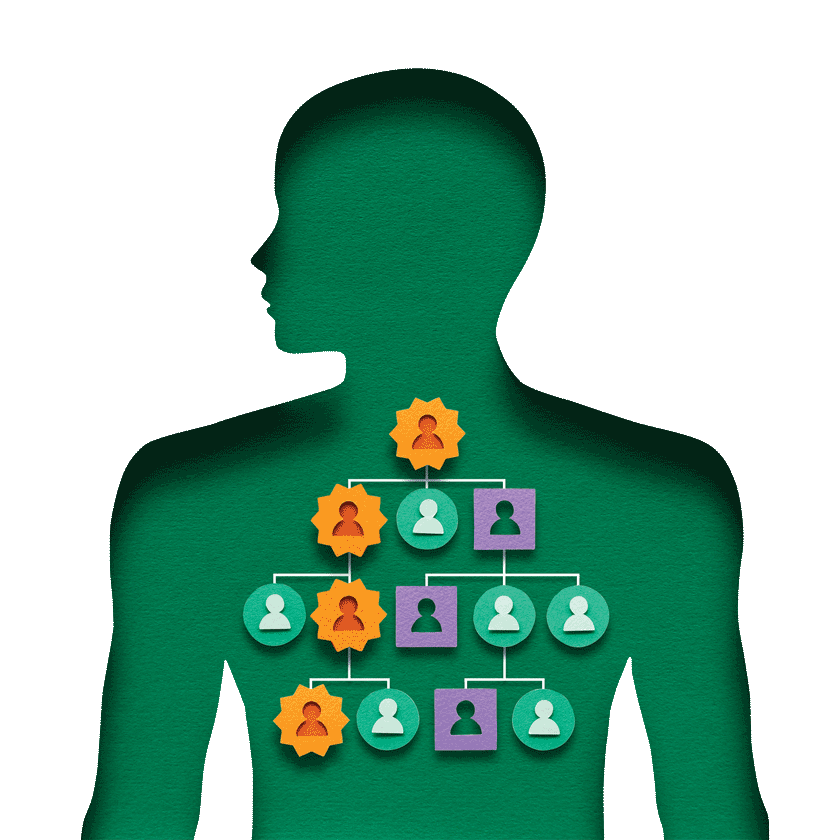

For years, scientists suspected the risk of developing certain forms of cancer was actually inherited.

In a landmark discovery more than 20 years ago, researchers proved their suspicions right with the discovery of two genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are linked to inherited forms of breast and ovarian cancers.

Today, due to that discovery, there have been significant advances in improved screening and treatment decisions for women who have inherited these mutations. Those advances give women not only better chances at survival, but also a better chance at preventing breast and ovarian cancer.

But ongoing research into BRCA shows these genes play a role in several cancers, and can put women—and men—who have inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations at increased risk of pancreatic cancer. BRCA mutations increase the lifetime risk for pancreatic cancer in both men and women from 4.5 percent to 7 percent, versus 1.5 percent risk in the general population.

These mutations are rare, accounting for only about 5 to 8 percent of the general population of patients with pancreatic cancer. But the occurrence of BRCA mutations can be as high as 10 to 15 percent for those of Ashkenazi heritage, says medical oncologist Dr. Eileen O’Reilly, Associate Director for Clinical Research, David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), New York.

The hope is that someday pancreatic cancer patients who harbor these mutations may also benefit in the same way that those with breast and ovarian cancer are benefiting today, she adds.

It’s All About DNA Repair

The primary job of BRCA genes is to make sure the DNA in each cell is functioning properly and to repair any damage that may occur. However, when these genes are mutated, they can’t do their job of correcting DNA damage. In turn, this accumulated damage can lead to cancer.

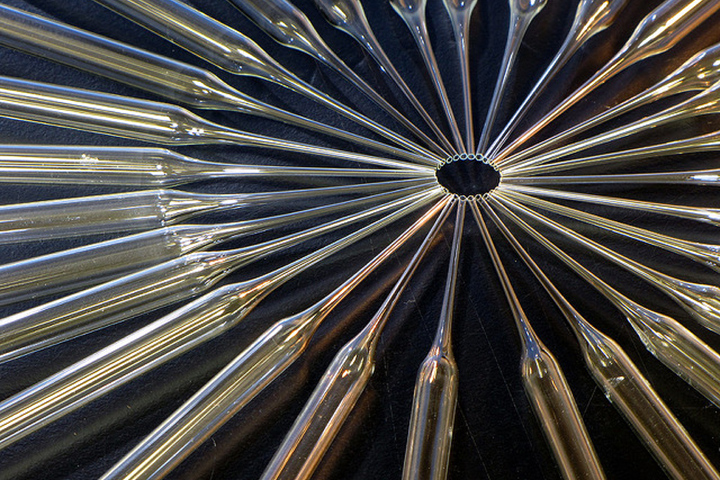

However, since pancreatic cancer patients with BRCA mutations (as well as breast and ovarian cancer patients) have DNA repair deficiencies, they may benefit from selective treatment, such as platinum-based chemotherapies alone, or in combination with a new class of drugs called PARP inhibitors, explains O’Reilly, who has also served as principal investigator of multiple phase I, II, and III trials in pancreatic cancer.

That’s because these treatments target DNA-repair problems. For example, platinum-based therapies, such as cisplatin, specifically target tumor cells by binding to DNA strands. When this occurs, cells can’t replicate and will die.

But our genes also have a kind of backup system to fight DNA damage. That’s where PARP molecules enter the picture. Essentially, they help with DNA repair, which occurs normally, and regularly in your cells—but more often in cancer cells. And when PARP inhibitors are used with DNA-damaging agents, the combination prevents the cancer cells from fixing faults in their DNA.

Early Trials Promising

Scientists are now exploring the role of PARP inhibitors alone or in combination with platinum-based drugs and other agents. “We still have a lot to learn about BRCA-mutated pancreatic cancer especially in terms of genetic makeup, the types and frequency of mutations, and mechanisms of resistance to platinum-based therapies and PARP,” O’Reilly says. But early-stage trials are promising.

In May 2016, medical oncologist Dr. Susan Domchek, Executive Director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Basser Center for BRCA, in Philadelphia, presented data from a PARP trial at the annual American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2016 oncology conference. The study included 19 pancreatic cancer patients who had BRCA mutations and were treated with a PARP inhibitor called rucaparib. These patients (11 men and eight women) had relapsed despite as many as three prior chemotherapies. Results showed 32 percent of patients showed some benefit, with one patient having a complete response, two patients with partial tumor shrinkage, and four with stable disease.

At a prior ASCO conference, O’Reilly presented data from an early trial of 17 patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. These patients were treated with a PARP inhibitor called veliparib, in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine. This triple-combination showed high-activity in BRCA-related pancreatic cancers, and yielded a disease control rate of more than 88 percent.

Both Domchek and O’Reilly emphasize these trials have only involved a small number of patients, and that more ongoing trials are necessary. “This is not a cure, but we are hopeful that this particular group of patients (with BRCA mutations) will do better for longer periods of time,” says O’Reilly. “It’s a population who can benefit from this more targeted approach.”

Domchek agrees. “We are really at the beginning of our understanding, not close to the end. But I am excited and I am hopeful,” she says. “The ability to get sustained responses and improve the quality and quantity of life for our patients is really very exciting.”