COMBATing Pancreatic Cancer

Although long-term survival of pancreatic cancer is inching up, the disease remains extremely challenging.

One area of research that’s been especially difficult is that of immunotherapy. While other cancers, including melanoma and lung cancer, among others, have had some remarkable advances with immunotherapy, pancreatic cancer remains stubbornly difficult. One reason for this seeming lack of efficacy is that pancreatic tumors tend to be nonimmunogenic. That means the cancer does not elicit a strong immune response. Scientists often refer to pancreatic tumors as being “cold.” Their goal: make the tumors more amenable to immunotherapy, or “hot.”

One study showing promise is called the COMBAT trial. The COMBAT/KEYNOTE-202 phase IIa is for patients with unresectable metastatic pancreatic cancer whose disease has progressed after failing first-line gemcitabine-based treatment. In this latest iteration of the COMBAT trial, study participants receive a triple combination of treatments, which includes treatment with an agent called BL-8040 (monotherapy priming treatment) for five days, followed by combination cycles of chemotherapy (irinotecan liposome injection/5-fluorouracil/leucovorin), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and BL-8040 until progression. The COMBAT study was originally designed as an open-label, multicenter, single-arm trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combination of BL-8040 and pembrolizumab, an anti-PD-1 therapy, for patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

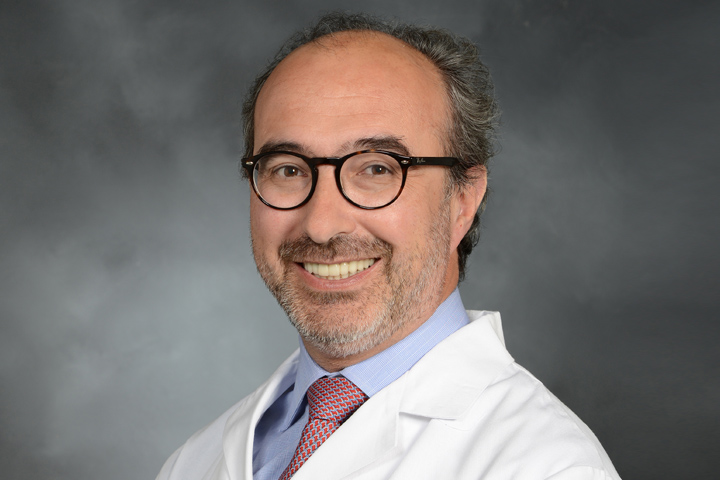

“The issue with immune therapy is that it can work nicely in other phenotypes, but it doesn’t work for pancreatic cancer so far, explains COMBAT’s principal investigator Manuel Hidalgo, M.D., Ph.D., Chief of the Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology and a senior member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York.

“The strategy behind the COMBAT trial is to facilitate an entry for the immune cells to infiltrate the tumor. In other words, we want to boost immune activity. One of the reasons why pancreatic cancer may not be sensitive to immune therapy is that there are no immune cells there. We’d like to change that.”

A Primer on Pembrolizumab and BL-8040

Pembrolizumab is better known by its brand name Keytruda. It’s a checkpoint inhibitor that has been approved for numerous cancers, including unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with a specific biomarker—microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficient (dMMR). A small percentage of pancreatic tumors fall into that category.

Pembrolizumab works by helping the body’s own immune system kill cancer cells. In a perfect setting, the immune system can detect and target an abnormal cell for destruction using T cells. However, to prevent T cells from attacking the body’s own cells, the immune system has a series of checkpoints to stop the T cells from also attacking healthy cells. The PD-1 pathway is one of these checkpoints. Some cancer cells find a way to hijack this pathway and escape the immune response. Pembrolizumab is a monoclonal antibody designed to identify and block a receptor on PD-1. By blocking PD-1, the T cells can then seek out the cancer cells and kill them.

BL-8040 is a short synthetic peptide that acts as an antagonist for the receptor CXCR4, which is expressed on many tumor types. CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12 are also important for maintaining tumor cells in close contact with the stroma. In some research, these receptors are correlated with poor prognosis. In some preclinical and clinical work, BL-8040 shows the ability to turn “cold” tumors, like pancreatic cancers, “hot,” sensitizing those cancers to immune checkpoint inhibitors, explains Hidalgo.

Results Are Promising

Updated data from the triple combination arm of the phase IIa COMBAT/KEYNOTE-202 study was presented at the ESMO Immuno-Oncology Congress.

- A total of 36 out of 40 patients were enrolled in the study. As of December 5, 2019 (the cutoff date for data presentation), 30 patients were able to be evaluated for safety and 22 were able to be evaluated for efficacy. All study participants had progressed following first-line treatment with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy.

- Best response for the evaluable population of 22 patients showed seven partial responses (PR) and 10 stable disease (SD) patients, resulting in an overall response rate (ORR) of 32 percent and a disease control rate (DCR) of 77 percent. Current chemotherapy standard-of-care treatment in second-line patients has an ORR of 17 percent and DCR of 52 percent, so these results compare favorably.

- Five patients with stable disease became partial responders as treatment continued. Out of the seven partial responders, five were still on the treatment, with a current maximum treatment time of more than 330 days, and four responders showed a reduction in tumor burden of more than 50 percent.

- The median duration of clinical benefit until progression for the 17 patients with disease control is 7.8 months. Progression-free and overall survival data remain on track for mid-2020.

- The combination was generally well-tolerated.

“Metastatic pancreatic cancer just does not respond well to chemotherapy alone, and so far immunotherapy used alone has not shown any effect either,” says Hidalgo, who says these initials results are “promising.”

That’s because overall response rate of these study participants is almost double the current chemotherapy standard-of-care treatment for second-line patients, he explains. The results are also boosted by the extended durability of clinical benefit, a median of 7.8 months, when compared to the approximately three months of typical response duration for other treatments used in second-line pancreatic cancer.

Survival data is on track for mid-2020. “It’s fair to say I am cautiously optimistic,” Hidalgo says. “The caution comes because we have not treated all that many patients and we need to keep gathering more information.

“There sometimes is the thought that nothing works in pancreatic cancer. This may indeed work in pancreatic cancer but we just don’t know yet. This is just one area we are looking at, but I think it might be a good one. I think what’s become more clear is that combination therapies, especially with immune therapy, might result in much better treatments for patients.”