Why You Need This Simple Blood Test at Diagnosis

Measuring a patient’s levels of CA 19-9, a pancreatic cancer tumor marker, right after diagnosis can help doctors tailor treatment, new research suggests. Here’s why.

For most pancreatic cancer patients, the days leading up to and after diagnosis involve a whirl of physical exams, imaging scans and blood tests.

Amid the chaos—and the shock of the news—many patients aren’t armed with all the questions they ought to ask when they sit down with their oncologists for the first time.

It can take a moment to get one’s bearings. But researchers at Rochester, Minn.’s Mayo Clinic say that there’s at least one question every patient should bring up with his or her oncologist immediately after diagnosis: What’s my CA 19-9 level?

The Importance of the CA 19-9 Level

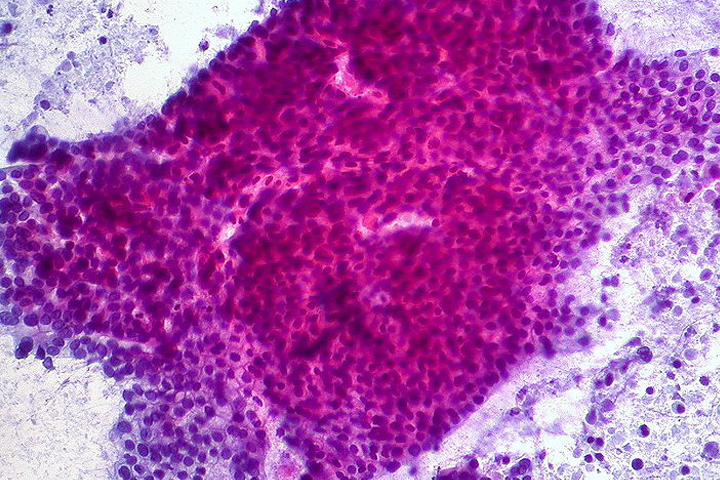

The protein CA 19-9 is a tumor marker often used by doctors to confirm a pancreatic cancer diagnosis or monitor a patient’s progress through treatment. Unfortunately, test results aren’t always clear-cut: CA 19-9 levels can rise with noncancerous conditions, like pancreatitis, and with other cancers. While 90 percent of us produce CA 19-9 normally, ten percent of us don’t—and therefore wouldn’t test for elevated levels even in the presence of pancreatic cancer. For those reasons and others, the marker isn’t sensitive enough to rely on for screening.

But the implications of elevated CA 19-9 levels may be much further-reaching than doctors once thought, says Mark Truty, M.D., a gastrointestinal surgical oncologist at Mayo and the lead author on a provocative paper presented last November at the Western Surgical Association annual meeting in Napa, Calif. and published this winter in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Using the National Cancer Database, Truty and his team retrospectively looked at the cases of 113,145 pancreatic cancer patients and found that only 25% received a CA 19-9 blood test at diagnosis, independent of their cancer stage.

More strikingly, Truty and his colleagues also observed that patients with elevated CA 19-9 levels had significantly worse survival outcomes than patients at the same cancer stage whose levels were lower.

Next, Truty and his team combed the records to determine whether patients with elevated CA 19-9 levels who received chemotherapy before surgery had better survival outcomes than patients with elevated CA 19-9 who immediately had surgery.

What they found stirred them. Indeed, chemotherapy prior to surgery (also known as neoadjuvant therapy) seemed to have a major positive impact on survival—and was the only treatment sequence, Truty says, that completely “eliminated the increased risk posed by their high CA 19-9 levels.”

A Paradigm Shift

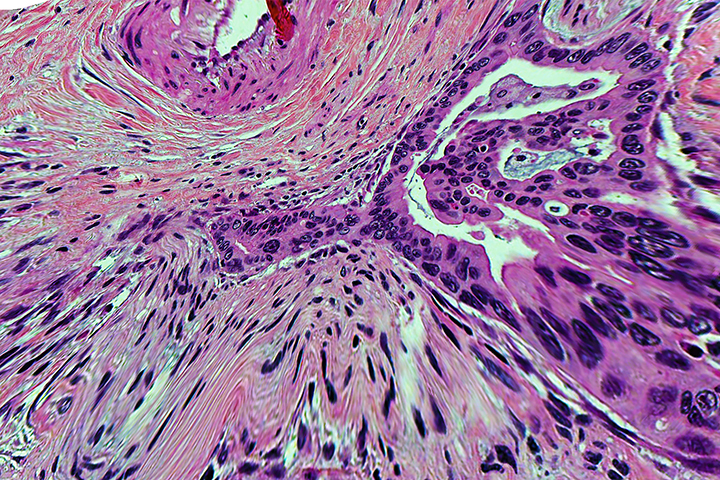

For years, doctors have regarded surgery as the best, most effective first-line intervention for patients with pancreatic cancer. Somewhat controversially, Truty’s team is calling that long-held belief into question. The standard surgery for pancreatic cancer—the Whipple procedure—is a long, complex operation with substantial risk for complications.

Truty’s group’s findings suggest that even when a patient’s pancreas tumor looks operable, doctors should stop and assess whether it would be better to give chemotherapy first, by checking to see if their CA 19-9 levels are high.

“We want to do everything possible to identify which patients will most benefit from surgery,” Truty notes. “[Our research indicates] that patients with any elevation of pre-operative CA19-9 above normal should have chemotherapy before any attempt at an operation. By identifying higher risk patients and giving them chemotherapy right away, before the operation, we can really maximize the survival benefit they’ll get [when they eventually have] surgery.”

It’s not definitively clear as to why preoperative chemotherapy seems to improve survival in patients with elevated CA 19-9. The working theory, says Truty, is that CA19-9 elevation may indicate that the cancer has spread to other areas, even though metastases aren’t yet visible on scans.

“We call this micrometastasis,” he says. Among cancers, pancreatic has one of the highest recurrence rates. “Often patients who get an operation for early stage pancreatic cancer will develop new tumors in the liver, lungs, or in other areas within two years of surgery,” Truty notes. Doctors believe that tiny metastases may play a role in the cancer’s tendency to reappear. Systemic chemotherapy may head off recurrence by eliminating those possibly hidden micrometastases right away, before they do damage.

Truty’s team’s findings may stir debate in the pancreatic cancer research world. For one thing, notes John Chabot, M.D., F.A.C.S., executive director of the Pancreas Center at Columbia University Medical Center, “We can only theorize that micrometastasis exists, because micrometastases are smaller than we can detect with our scanning tools.”

And changing the standard first intervention for patients with operable pancreatic cancer from surgery to chemotherapy (if they have elevated CA 19-9) is going to require a major paradigm shift, Chabot adds.

“If in fact the Mayo group is showing us that preoperative chemotherapy eliminates micrometastases, it will take a huge mental leap for all of us [to accept that],” says Chabot. “I need to see more data to agree that neoadjuvant chemotherapy [should be given] based on [elevated levels of] CA19-9 alone. We need to accumulate strong data, have it analyzed thoroughly and go through the entire validation process.”

But Truty—whose team is now working on developing new treatment approaches based on their findings—believes that he and his colleagues are onto something.

“As chemotherapy continues to evolve, we need to figure out how best to sequence all the available options for pancreatic cancer patients,” he says. New, soon-to-be-published data from Truty and his colleagues suggests that only 1 in 5 patients actually derive “significant perceived benefit” from the standard surgery-first approach. “One in 3 actually have worse outcomes, compared to non-operative therapy,” he says.

“This data is compelling, controversial, and will challenge the status quo—and hopefully lead to new hope and major changes in pancreatic cancer care.”