Picking a Clinical Trial for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment

- Minor GI symptoms turn out to be stage II pancreatic cancer

- Treatment plan: a clinical trial

- Overcoming significant medical challenges

In retrospect, some symptoms appeared, but I was somewhat oblivious—I had lost some weight, but as my new Fitbit would suggest, I was trying to lose weight at the time.

I was having some minor gastrointestinal issues, but my doctor initially had me take a probiotic. After two months of no improvement, I was placed on a low-FODMAP diet (avoiding foods that are harder for the body to digest—this diet is frequently followed to reduce the digestive symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome). After two months on this diet I still had the GI issues. Although I did not have any of the more common symptoms of pancreatic cancer (jaundice, abdominal or back pain) my wife finally insisted I see a specialist. One CT scan later, my initial diagnosis was confirmed: stage II pancreatic cancer, located in the head of my pancreas. It was July 2, 2014 and I was 54 years old.

Experience Helps Me Choose

As a two-time cancer survivor (testicular cancer in 1991; liposarcoma in 2010), I was not shocked by this news, but it is always a jolting experience to hear “You have cancer.” My previous experience with cancer and my career in pharmaceutical research and development gave me some knowledge of the next steps to take.

My first decision was to find a surgeon and determine if I was eligible for a Whipple procedure. I knew that only a small percentage of patients are eligible for a Whipple, because the disease has often advanced too far when diagnosed. I sought advice from my pharma colleagues, and the message was consistent and clear: “You don’t just want an excellent surgeon, you want a surgeon who specializes in pancreatic cancer and has performed hundreds of Whipple procedures.” I selected the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia) for my treatment: my doctors were Dr. Jeff Drebin (now at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York) as my surgeon, Dr. Ursina Teitelbaum as my oncologist, Trish Gambino as my nurse navigator, and Dr. James Metz and Erin Davis for radiation oncology.

I was lucky my cancer had been diagnosed early, so I was Whipple-eligible, but we faced our first significant treatment decision—whether or not to participate in a clinical trial. This is no trivial choice. As a patient, I am not wedded to any particular company or medical institution; I am motivated by what medical option is best for me and my family. But with a disease like pancreatic cancer, where the survival numbers are quite depressing, I was very open to being very aggressive in my treatment. Dr. Drebin suggested I consider a clinical trial sponsored by Stand Up To Cancer, designed to assess the effect of high doses of vitamin D given in conjunction with chemotherapy.

The Differences Between Standard Treatment and the Clinical Trial

Practically for the patient, there were two main logistical differences to standard protocols by participating in the trial. First, the sequence of treatment was different. The standard protocol at my institution was to have surgery followed by eight weeks of recovery and then chemotherapy. However, the research protocol was designed as one presurgical round (four weeks) of chemotherapy followed by the Whipple procedure, with its eight-week recovery. After recovery from the Whipple, there would be three additional post-surgery rounds of chemotherapy. (Note: recently presented data suggests that one round of chemotherapy presurgery can be beneficial).

Second, there were three trips per week to the hospital for one chemo infusion of Abraxane and gemcitabine, plus three vitamin D infusions. The standard protocol has one trip to the hospital for the chemo.

Several “second opinions” I received suggested not participating in the study—to just “cut the tumor out” as soon as possible. However, I opted to participate in the study for three reasons:

- It seemed more logical to me, given the long recovery time for the surgery, to start attacking any cancer immediately that might have spread beyond the tumor itself. This opinion was not necessarily scientifically supported, but just felt better to me.

- There was early evidence, though far from statistical significance, suggesting that the vitamin D might actually stabilize the tumor, even shrink it.

- I wanted to “pay it forward.” There is little data available on pancreatic cancer because tumor removal is only a viable option for a very small number of patients. I believe that the science in this area needs to progress and hope that future patients are able to benefit from any future insight obtained.

Given my medical history and my desire to be aggressive, Dr. Teitelbaum suggested that I should follow up my four rounds of chemotherapy with additional radiation. However, given my radiation treatments during my previous cancers, I needed radiation that was very targeted. The University of Pennsylvania is a leader in proton beam therapy and we coordinated with Dr. Metz’s team for 28 treatments of proton beam radiation over two months, plus chemotherapy with Xeloda.

Coping with Side Effects

During my treatment, I avoided the nausea often experienced during chemotherapy (though I now struggle with boat rides on choppy waters). I did suffer from excessively soft fingernails and from neuropathy in both my feet and hands. I continued to have GI issues, which I believe will just be part of my new normal.

I also faced a number of less common but very debilitating side effects after my treatments. I recently celebrated my five-year anniversary and Dr. Teitelbaum told me that I am cancer-free, but in the next breath, she added how frustrating all my side effects have been to her and my medical team. The side effects included:

- Significant internal bleeding that led to many emergency room visits, blood and iron transfusions, and ultimately resulted in more major GI surgery to fix the problem.

- Suffered from malnutrition and ascites that led to infusions of Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) for several months; this resulted in my losing 40-plus pounds.

- Contracted a bacterial infection, likely from my peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line for the TPN feedings.

- Diagnosed with shingles (and yes, it is as painful as everyone says).

- Had a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure, used to reduce portal hypertension and its complications, especially variceal bleeding. I also had a small wire-mesh coil (stent) inserted into a liver vein.

I don’t know if any or all of these side effects are connected to my treatment or to my pancreatic cancer. But as the old song goes, the “hip bone is connected to the thigh bone and. . . . ” But in the grand scheme of things I am here and doing well.

Lessons Learned from Pancreatic Cancer

Lesson #1: The silver lining for me—was that my cancer was caught early. Take action. We are all busy and it is far too easy to avoid seeing a doctor. Don’t wait! In my case, it probably was the difference in being diagnosed with stage IIB cancer vs. something far more advanced.

Lesson #2: Do your research. Get multiple opinions and work with the best medical team. This can be a tough ask, particularly if you are dealing with a team of physicians as I was. I needed a surgeon with significant experience in performing Whipple procedures. I needed a radiation oncologist who was “current” on the wide variety of therapies available. I needed an oncologist to quarterback my plan and care. And, just as important, it took an active caregiver and patient to pull everything together. A key challenge of Lesson #2 is the complicated logistics involved. Most cutting-edge research and treatments are typically found at larger hospital networks, often located in major cities, which may not be convenient nor viable for many patients. You should be prepared to challenge the system and determine a way, if possible, to obtain a majority of your treatments as close to home as possible. Alternatively, explore all options, including participation in clinical trials, to try to minimize your cost burden if you must seek treatment away from home.

Lesson #3: Seek normalcy at every turn. The journey is far from normal and will stress every aspect of your life. Realize what is happening and adjust as best you can. During chemotherapy, the patient often falls into a pattern—for me, treatment on Day 0, feeling good on Day 1 but out of sorts by Days 2 and 3, reduced energy later in the week until it all started again next week. I lived around these tendencies, knowing that any given week might be different. Another aspect for maintaining my normalcy was to work. I needed the mental distraction of focusing on something other than my medical situation all of the time. Everyone is different, but remember it is important to realize your limitations in pursuing “normalcy.”

As the great baseball player (and even greater quote machine) Yogi Berra once said, “It ain’t over `til it’s over!” Never have truer words been uttered regarding the patient journey. There is diagnosis, treatment, and recovery. But there’s more! I write a blog called Through the Patient Lens, and in one article co-authored with Lori Abrams, we discussed the new phase of care, which we called the “New Normal.” We highlighted how we each managed our diagnoses, treatment, and recovery. With all the medical challenges, I was lucky to survive, and post-recovery I was living a new normal, a lifestyle that was medically impacted on an ongoing basis and different from my former life. We highlighted how we managed our diagnoses, treatment, and recovery, both of us with very different medical challenges and lucky to have survived, but we explained that post-recovery we were each living a new normal, a lifestyle that was medically impacted on an ongoing basis and different from our former lives.

After chemotherapy and proton beam radiation, my plan called for scans every three months for the first two years and then every six months beyond that. These were anxious times of “scanxiety” as I waited for a thumbs-up or thumbs-down assessment. But as my oncologist once told me, if my problems were only related to my cancer, it would be much easier. The last few years have seen nothing but curveballs, with 13 trips to the ER and some major health problems that are likely related to the pancreatic cancer. My body has barely had the opportunity to fully recover before the next challenge appears.

Lesson #4: Amplify the patient voice. This is very important to me given my background in pharmaceutical research and development and my experiences as a patient. I participate on an Oncology Patient Council at GlaxoSmithKline to provide input to researchers and clinicians to better integrate the needs of the patient. I also participate on the University of Pennsylvania Patient and Family Advisory Council to provide patient perspective/insight in delivering healthcare solutions and contribute to the recently formed Pancreatic Cancer Research Center at Penn. I also work with the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN). It is important to help other patients and future patients.

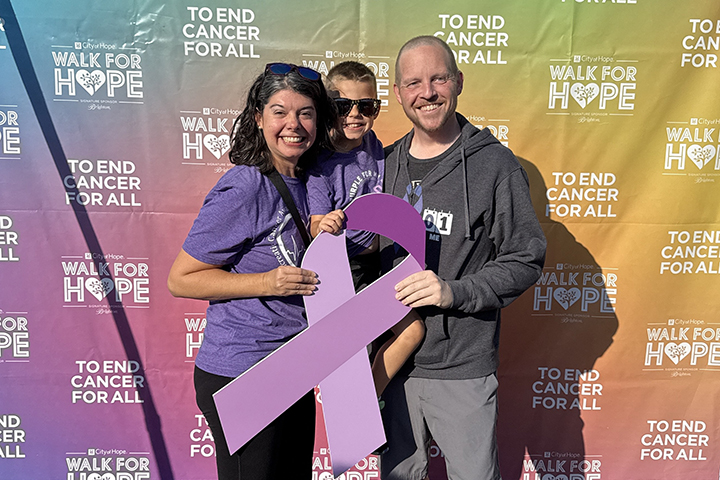

Lesson #5: The caregiver is so important. It is essential to have an excellent medical team who are extraordinary clinicians that have the trust and confidence of the patient and caregiver and can work seamlessly in partnership. But as I have said often, it is the caregiver who brings it all together. For me, my wife coordinated everything—and I mean everything. She was able to maintain our balance, at least what was possible in these most trying times. She allowed me to focus on dealing with my disease. I will be forever indebted and have built a long list of IOUs of missed events.

So, a toast to all of the caregivers and the support they provide; and a toast to my extraordinary doctors and medical professionals, who were as focused and aggressive as I was; and a toast to all of those patients who allowed me to stand on their shoulders and feel 20 feet tall; and finally a toast to the healthcare system and the miracles they enable every day. Hopefully we can make these miracles available to everyone at a more reasonable cost over time.