The Promise of Organoids

Lustgarten Foundation

Malignant tumors like pancreatic cancer exist in the human body as three-dimensional structures. This structure is influenced by its microenvironment, a kind of ecosystem in which the tumor grows.

To learn more about the biology of tumors like pancreatic cancers, scientists have long studied malignant cells in two dimensions in a flat, laboratory-based cell culture system like petri dishes or slides. Although scientists gleaned important information that has influenced how pancreatic cancer is treated, this method is limited. For example, scientists could learn little about how the tumor actually functioned within the human body.

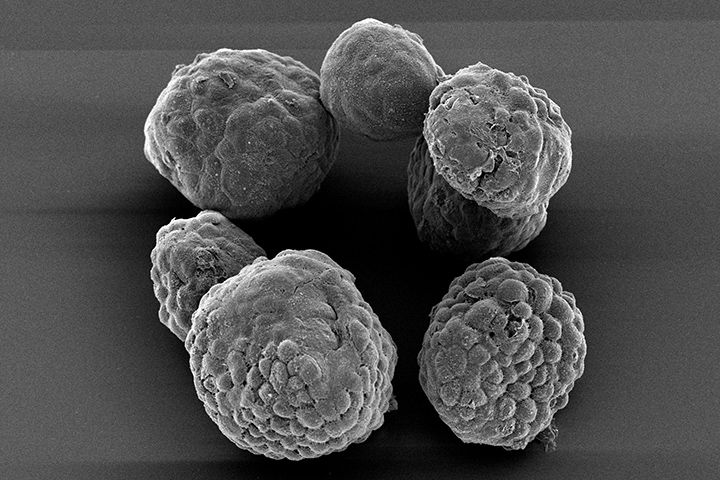

But over the last several years, with the help of organoid technology, science has taken a big leap forward in its understanding of what makes pancreatic tumors so difficult to treat. Although it may sound like science fiction, these organoids are grown right from the cells taken from a patient’s tumor. The end result is a three-dimensional cluster of cells, a kind of “mini-tumor,” that looks and acts similar to the tumor that is growing inside that particular patient.

“Pancreatic cancer is a highly aggressive disease. For our patients with pancreatic cancer, we need to find the drug or combination of drugs that will be more effective in an individual patient, based on their particular tumor,” says Brian Wolpin, M.D., M.P.H., the Robert T. and Judith B. Hale Chair in Pancreatic Cancer at Boston’s Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center. “We and others are in the early stages of using organoids in this way to match the appropriate therapies to patients based on the sensitivity of organoids to drugs in the laboratory.”

Growing an Organoid

All cancer research relies on a steady supply of cells—both normal and cancerous—that can be grown in the laboratory. By comparing normal cells to cancer cells, scientists can then identify the changes that lead to disease. However, pancreatic cells have been extremely difficult to culture in the laboratory.

Furthermore, the normal ductal cells that are able to develop into pancreatic cancer represent only about 10 percent of the cells in the pancreas, complicating efforts to pinpoint the changes that occur as the tumor develops. Until now, scientists have had limited success culturing human ductal pancreatic cells under standard laboratory conditions. But about four years ago, researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, along with a Dutch research team, developed a method to grow pancreatic tissue not only from laboratory mouse models, but also from human patient tissue, offering a path to personalized treatment approaches in the future.

The Creation of an Organoid

From that groundbreaking research, the efficiency of growing a patient’s pancreatic cancer in the laboratory has greatly increased. If a patient agrees, tumor samples are first isolated during biopsy. Then specialized digestive enzymes are added to break down the samples into single cell suspensions, which are then added into a culture dish along with a specialized gel material. These single cells grow into organoid clusters. In about eight to 10 weeks, a sufficient number of organoids are often present to test sensitivity to dozens of drugs. Given the limitations of prior approaches to growing pancreatic cancer in the laboratory, this is a relatively short amount of time, explains Wolpin. However, studies are ongoing to further reduce the time necessary to identify drug sensitivity using organoids.

After the organoids are growing sufficiently, they are tested with various drugs to see how they respond to different drug cocktails. The goal is to determine whether organoid drug sensitivity can be used in real time to guide treatment decisions and whether organoid drug sensitivity predicts patient clinical response. It’s important to note these tumor organoids are heterogeneous. That means there are differences between tumors of the same type in different patients, and between cancer cells within a patient’s tumor. Both of these factors can lead to different responses to therapy.

“We are currently evaluating the potential of pancreatic cancer organoids to personalize therapy for our patients. In particular, we are using organoid drug sensitivity testing to guide patient enrollment on new treatment options being offered in clinical trials,” says Wolpin, who is also Director of the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center and Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

The Future of Organoids

As this work proceeds, Wolpin thinks organoids will have a place in not only continuing pancreatic cancer research but also in more tailored patient care. “We understand that pancreatic cancer remains difficult to detect and treat, but we are making progress and none of the scientists or doctors in this field are giving up,” he says. “Recent discoveries are providing hope for patients today, while generating new insights into the causes and progression of this disease, so that we continue to treat our patients more effectively in the future.”

“Those of us involved in pancreatic cancer research and patient care are trying to move beyond the place where all patients receive the same treatment program. We absolutely need to get to a place where treatment is tailored to that individual and the characteristics of their specific cancer. Organoids may be able to help us to do that.”