Cachexia Research Showing Promise

The muscle wasting disease called cachexia occurs in about 80 percent of people with advanced cancer.

It’s especially prevalent among those with pancreatic or lung cancer. Some estimates show that it may cause about 30 percent of cancer deaths, mostly because of heart or respiratory problems caused by extreme muscle loss.

Cachexia can be devastating for patients, leaving them fatigued and making simple tasks like shopping or showering often impossible. What is particularly tough for patients—and those who love them—is that the numerous metabolic and immune system changes caused by cachexia cause a patient’s tumor to eat away at the body. This causes dramatic changes in physical appearance, adding an acute emotional toll to an already seemingly insurmountable physical toll.

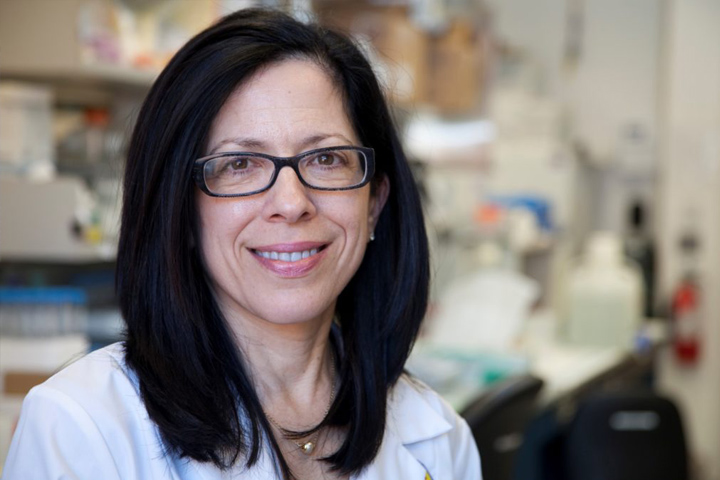

For years, cachexia didn’t get much attention. But researchers throughout the world are starting to hone in on a better understanding of the complicated biology accompanying the disease, in hopes of finding targets that can be exploited to reverse or even stop cachexia. “What we want to do in our lab is to help change the standard of care for patients,” says Teresa Zimmers, Ph.D., Professor of Cell, Developmental & Cancer Biology at Oregon Health & Science University and the Knight Cancer Institute, both in Portland. “There’s a lot of interest in cachexia right now and the research is all focused on helping patients with what was once just considered a terrible side effect of cancer and other diseases like COPD and heart failure. People used to think that not much could be done about it, but now we are truly starting to understand the underlying mechanisms that cause cachexia. And from there treatments can be developed. I am hopeful about the future.”

Unraveling Basic Biology

At the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Special Conference in Pancreatic Cancer Research in mid-September 2024, Zimmers spoke about the various biological mechanisms of pancreatic cancer cachexia. Among the targets researchers are studying is a protein called IL-6, or interleukin-6. It’s implicated in many physiological processes, including the immune response, inflammation, and brain function. In cachexia, IL-6 is a primary mediator of inflammation in muscle atrophy, binding to its receptor which then activates numerous pathways causing the loss of muscle protein, Zimmers explained. Circulating levels of IL-6 are associated with weight loss in cancer patients and also with reduced survival.

She reported findings of a randomized phase II trial testing the efficacy of gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (gem/nab) with or without tocilizumab (toc), as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer, the reporting of which is currently under review. In patients with advanced disease, the addition of tocilizumab to gem/nab did not result in improved overall survival rate at six months. Although more patients were alive at 18 months in the gem/nab/toc arm, long-term survival rates exceeding 24 months were not different between groups.

However, in cachexia endpoints, there was no difference in weight loss at two or four months. But muscle loss was prevented with tocilizumab compared to the placebo. There was also an increase in the proportion of patients who gained or had stable muscle mass. There was no change in fat tissue (adipose) loss.

The trial did provide evidence that IL-6 can mediate muscle loss and provides an opportunity to continue to look for markers of response to therapy and to identify additional targets. “The takeaway for me is that cachexia can be driven by IL-6 and we need to use that information on how to move forward,” adds Zimmers, who is also co-founder and past president of the Cancer Cachexia Society. “This is not going to change standard of care, because there were serious side effects and overall survival was not improved. Perhaps we’ll find out it’s more important to intervene with patients who have earlier disease stages or maybe there is a better combination therapy. We need to figure out where to go from here.”

Promising Results

Among the most promising of potential cachexia treatments is a study of three doses of a Pfizer experimental monoclonal antibody called ponsegromab compared to placebo in 187 people with non-small cell, pancreatic, or colorectal cancer as well as elevated serum GDF-15 concentrations. Almost three-quarters of participants had stage IV cancers.

GDF-15, or growth differentiation factor 15, is a key driver of cachexia. It’s a protein that binds to a certain receptor in the brain and has an impact on appetite. “We call GDF-15 the ‘misery hormone’ and in the past few years the field has really grown to understand just how important it is,” says Zimmers, who was not involved in the study and has consulted for Pfizer in the past. “It (GDF-15) seems to have evolved as a protective mechanism,” Zimmers explains. “Injury causes release of GDF-15 which signals in the brain to tell you that you’re not hungry and make you feel ill so that, in evolutionary times, you’d hide and not get eaten by a predator. Of course, we no longer need to hide when we are ill, and results in mice without GDF-15 and people who lack GDF-15 suggest that blocking it could be safe.”

Indeed, it seems that when all is operating well within the body, GDF-15 levels are low and it doesn’t play that big of a role in metabolic regulation. But when an injury occurs or tissues are under duress with cancer, infection, pregnancy, environmental toxins, or chemotherapy, GDF-15 levels rise.

After 12 weeks, patients in the study who took the highest dose of ponsegromab—400 milligrams—saw a 5.6 percent increase in weight compared with those who received a placebo. Patients who took a 200-milligram or 100-milligram dose of the drug saw about a 3.5 percent and 2 percent increase in body weight, respectively, compared with the placebo group. There were also associated moderate improvements in appetite and cachexia symptoms and increased physical activity also observed in ponsegromab-treated patients, relative to placebo. At the high dose, there were significant improvements on measures of anorexia and activity, as well as in skeletal muscle.

Since the patients had advanced disease and typically would not gain weight, the results of the trial are “quite promising, but of course further trials are necessary,” Zimmers adds. To that end, based on these positive results, Pfizer is discussing late-stage development plans with regulators with the goal of starting registration-enabling studies in 2025, according to the company.

An Addition to Cachexia Guidelines

In 2023, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) released what is called a rapid recommendation update prompted by a placebo-controlled trial from researchers in India. In the study, researchers enrolled 124 patients with untreated, locally advanced, or metastatic cancers and randomly assigned them to 2.5mg olanzapine or to placebo once a day for 12 weeks along with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic.

Based on some positive data, such as a greater proportion of patients assigned to olanzapine having a weight gain of greater than five percent, ASCO says that “for adults with advanced cancer, clinicians may offer low-dose olanzapine once daily to improve weight gain and appetite. For those who can’t tolerate olanzapine, clinicians may offer a short-term trial of a progesterone analog or a corticosteroid to those experiencing loss of weight and/or appetite.”