New Gastrointestinal Screening Guidelines for High-Risk Patients

By the year 2030, pancreatic cancer is expected to be the second most common cause of cancer deaths in the U.S.

Although it is considered a relatively rare cancer, inherited gene mutations can increase a person’s risk of developing the disease. For most cancers, early detection contributes to longer survival. Yet the majority of pancreatic cancer patients are diagnosed in later stages, when surgery is no longer an option. That’s partly due to the fact that in earlier stages many people may not have symptoms indicative of pancreatic cancer, making it much more difficult to detect.

A new set of national guidelines published by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) was released in May 2022. These guidelines recommend annual pancreatic cancer screening for patients who are at increased risk because of genetic susceptibility. While earlier guidelines had restricted screening to only those individuals with BRCA1/2 mutations who had a family history of pancreatic cancer, this new set of guidelines now recommends screening for all patients with the gene variations, regardless of family history.

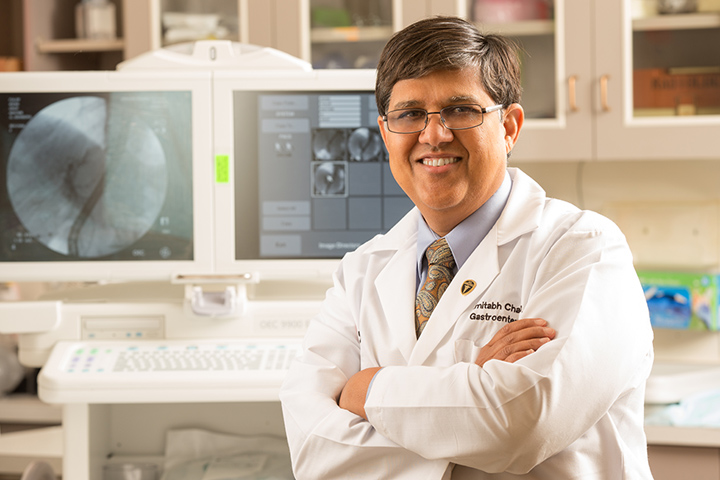

“Fewer than 25 percent of patients with BRCA1/2 who go on to develop pancreatic cancer actually have a family history of the disease,” explains gastroenterologist Amitabh Chak, M.D., Professor of Medicine and Oncology at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and the Brenda and Marshall B. Brown Master Clinician in Innovation and Discovery at University Hospitals UH Seidman Cancer Center (Cleveland, Ohion). “We would potentially miss some [pancreatic] cancers among this group if we only screen those with a family history of the disease.”

Although there’s no doubt screening of high-risk individuals may prove to be an important component of earlier detection, these new guidelines also highlight potential risks resulting from false positive screening test results. Providers are urged to counsel patients before enrolling them in a high-risk screening program.

Data Leads to New Guidelines

The first set of guidelines for high-risk screening started about a decade ago and was published in a number of gastroenterology journals. Those guidelines were created based on a consensus of experts, rather than any society or group, explains Chak. However, “these [new] guidelines are evidence-based,” he adds. “We started off with the belief that high-risk screening would be effective. But now we have data, rather than just opinion.”

For example, one study found that almost two-thirds of pancreatic cancers that develop in BRCA1/2 individuals would be missed if screening were limited to only those with a family history. Research also shows that pancreatic cancers in BRCA1/2 patients respond well to treatment with PARP (poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase) inhibitors. “One problem with family history is it is dependent on how big a family you have,” Chak says. “You may not have a large family and then you would miss out on screening. We also know that PARP inhibitors help treat this subset of patients and there will also be new agents. So it was worth expanding.”

As part of the guideline development process, researchers also looked at the potential harms of pancreatic cancer screenings. They found that screening tests such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasound were safe and low-risk.

However, the risk of undergoing surgery resulting from a false positive finding on either of these tests was also considered as part of the guidelines development process. “There is a small chance that a patient may undergo a surgery where nothing is found,” Chak says. “So undergoing surgery doesn’t provide any benefit, and surgery does carry risks.”

Talking to Patients Is Vital

Now that screening will be offered to potentially more people, it is vital that gastroenterologists and patients discuss both the pros and the potential cons of screening,” adds Chak, who is part of the Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Study (CAPS), a multi-institute research program developed to evaluate the effectiveness of early detection screening in high-risk individuals for pancreatic cancer and to research new biomarkers to improve early detection. A recent study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology shows that most pancreatic cancers diagnosed within the CAPS high-risk cohort in recent years have had stage I disease with long-term survival.

“Some people with no family history of pancreatic cancer but who do have a BRCA mutation will welcome this; some may not want to be screened,” says Chak. “People need to make the decision that is right for them with knowledge of both the pros and the cons.” There is evidence that suggests screening has a beneficial impact on patients; they have less anxiety compared to patients who don’t get screened.

Earlier detection of the disease is vital for those with genetic susceptibility but also for those without that susceptibility who don’t qualify for high-risk screening. “There is a real lack of noninvasive biomarkers that can help detect precursor lesions and early pancreatic cancer,” Chak explains. “There is a lot of research in this area, and I am hopeful.”

As a physician, Chak says one of the biggest benefits of screening is hearing from patients. “I’ve been part of the CAPS Consortium for high-risk screening for the last seven or eight years, and we have identified a couple of people with early cancers or dysplasias,” he says. “One of those patients is now three years out, and I received an email from her. She’s so happy that she came in for a screening. It’s one of those emails that makes you glad to be a physician.”