Surprising Clinical Trial Results in Pancreatic and Rectal Cancer

It’s unusual for those of us involved in cancer research to get too excited about early data.

We’ve seen too many trials that look promising fail in the longer-term. But there are always exceptions. In the past week, initial data for two very tough-to-treat cancers, specifically pancreatic cancer and rectal cancer, have made most of us sit back and say “Wow!” Although there are many questions that must be answered, further studies using these novel treatment approaches could drastically improve the lives of both pancreatic and rectal cancer patients as well as those with other types of cancer.

Proof of Principle for Pancreatic Cancer

In pancreatic cancer news, a small proof of principle trial involving two pancreatic cancer patients published in the New England Journal of Medicine resulted in tumor shrinkage of more than 70 percent for one of those patients, whose cancer had already spread to her lungs. Her disease remains stable one year after receiving this therapy approach. That’s exceptional, since treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer is very limited, and mortality rates for this stage of the disease remain extraordinarily high.

The researchers used a genetic engineering technique called T cell receptor, or TCR, therapy to target two very specific mutations. Scientists engineer a patient’s T cells to search out and find these mutations and once found, the T cells do their job to kill the cancer cells. The first mutation is called KRAS G12D, which is found in more than 36 percent of pancreatic cancer patients. But these patients must also have a very specific HLA type, or human leukocyte antigen, found on the cell’s surface. The goal is to boost the immune-fighting T cells to recognize and destroy a very specific mutated protein embedded in the malignant cancer cells. To be clear, these mutated proteins will only be found in patients who carry a KRAS G12D mutation and that very specific HLA type. It is not appropriate for all pancreatic cancer patients (more than 90 percent of whom harbor a KRAS mutation). However, the technology is so advanced that T cells can be engineered to find and kill other KRAS mutations and HLA proteins on cancer cells.

Using the T cell therapy approach, the researchers at Oregon’s Providence Cancer Institute, led by Eric Tran, Ph.D., re-engineered the two patients’ T cells so they could spot the mutated protein. The patient who responded had already received surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. She needed no further treatment and her response has been durable.

Researchers need more investigation to find out why, for example, one patient responded so dramatically while the other patient died. To help answer that question and others, the Oregon team has started another trial for TCR therapy for patients with incurable cancers with these mutations. Although this initial data reports on only two pancreatic cancer patients, it provides much-needed hope and solid information that more can and will be done to treat advanced pancreatic cancer in the near future.

An Astounding Rectal Cancer Trial

Last week, rectal cancer treatment got a huge boost during the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. There, Andrea Cercek, M.D. and colleagues at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center presented a study with astonishing results never seen by cancer clinicians or researchers. The standard of care treatment for rectal cancer includes chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, which results in a three-year disease-free survival rate as high as 77 percent, according to recent data. But this treatment approach is difficult and can cause substantial long-term problems, including bowel and sexual dysfunction, infertility, and neuropathy.

In this trial, researchers enrolled 18 people with stage II and III rectal cancer that is MSI-high or mismatch repair deficient. That means that the tumor cells are unable to repair damaged DNA and are less sensitive to the traditional treatment of chemotherapy and radiation. Approximately five to 10 percent of patients diagnosed with rectal cancer have cancers that are molecularly characterized as deficient in DNA mismatch repair enzymes.

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, has enrolled 18 patients with mismatch repair-deficient rectal cancer. These patients received immunotherapy instead of standard chemotherapy, radiation, and life-altering surgery. Twelve patients completed treatment and follow-up and all 12 patients showed a complete disappearance of their cancer. The other six patients’ tumors also melted away, but they are early into the follow-up period.

Most oncologists would agree that results like this are never seen—where every patient’s tumor disappears. It was a daring proposition by the study investigators to ask the participants to forego proven therapy and instead take immunotherapy with the programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor dostarlimab followed by non-operative care. Patients who did not have a complete response were to receive subsequent standard radiation therapy and chemotherapy; however, all patients had complete tumor resolution with dostarlimab, with only minor treatment toxicity. At a median follow-up of one year, none of the patients had needed other treatment, and none had experienced cancer regrowth. It is entirely too soon to know if this novel approach is curative or if this treatment approach can be extended to diverse patients. More studies are definitely necessary.

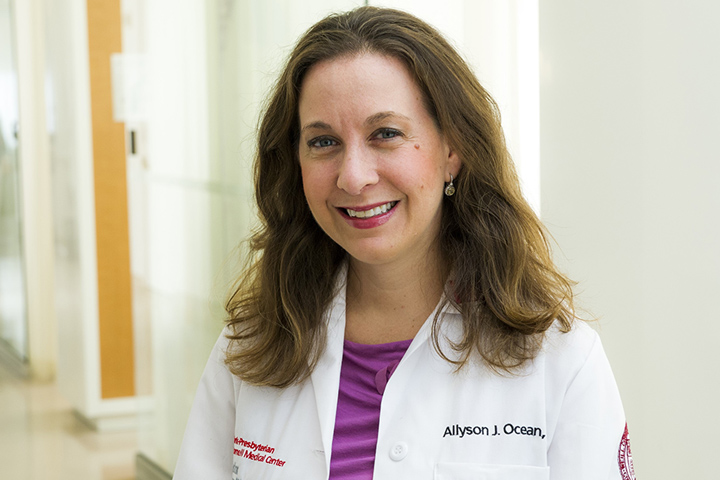

As a doctor who treats patients with gastrointestinal malignancies and as a scientist who helps to conduct clinical research in these areas, I am truly astonished at the progress being made in both understanding these diseases at their most basic molecular level and then translating that knowledge into promising treatments.

Allyson Ocean, M.D., is an oncologist specializing in gastrointestinal cancers at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She is the Chair of the Let’s Win scientific advisory board.