Fighting Pancreatic Cancer in a Petri Dish

Geoffrey Wahl and Christopher Dravis, National Cancer Institute/Salk Institute

For most patients, a pancreatic cancer diagnosis presents a race against the clock. Standard therapies can sometimes buy them months, but for those with advanced disease, meaningful, life-prolonging treatments are few and far between.

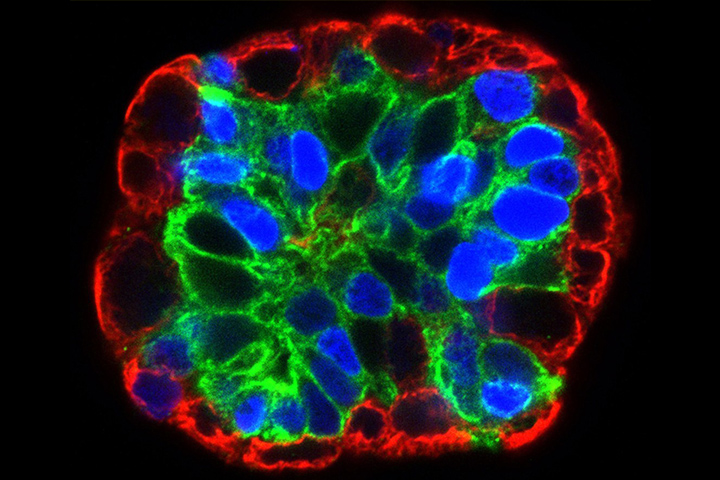

A new research technique developed at the Lustgarten Foundation Pancreatic Cancer Research Laboratory at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, NY, is aiming to change that. Three-dimensional pancreatic cancer organoids—tiny replicas of actual pancreatic tumors, cultured in petri dishes—are helping researchers hone and tailor treatments as never before.

Mini Tumors Called Organoids

Over the past several years, David Tuveson, M.D., Ph.D., director of research for Lustgarten and of the lab, and his colleagues have been fine-tuning a method for culturing and growing pancreatic tumor tissue outside of the body.

The theory? Testing treatments against a patient’s tumor in real time—at no risk to the patient—could show researchers what works and what doesn’t. Once a patient stops responding to a first-line treatment, the testing on her organoid could help her oncologist decide on her next intervention—and the next and the next, and so on.

“By growing their tumor tissue outside the body in a way that represents the tumors they were diagnosed with, then streaming medicines against them, you can see what works,” explains Tuv eson. “It’s a model system you can develop on each individual patient.” At this point Tuveson and his colleagues have developed roughly 30 pancreatic cancer organoids in the lab. The focus now is establishing proof of concept and figuring out whether the method is practical.

After taking a biopsy of a patient’s tumor it can take “a few days to a few weeks to grow the organoids, depending on the quality of the tissue sample,” notes Tuveson. “The challenge for patients is that some get sick so quickly, they don’t have very much time. Patients need to know within a few days or a week what’s the best way to take care of them. So the challenge we have is whether this method will be of practical use. Will this benefit everyone, or just people who can get an operation and have time to figure things out?”

New Pathways

Although the lab’s research is still in its early stages, preliminary findings have been revealing. “Already we’ve learned about new pathways, the processes cancer cells use to cause disease, that are important for the development of pancreatic cancer,” says Tuveson. “We’ve also been using the organoids to develop new diagnostic methods. And we’ve found some new medicines. They’ve been a wellspring of information.”

In 2015, months after she was diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer, Let’s Win founder Anne Glauber became one of the first patients to donate tissue for Tuveson’s organoid research. Getting the chance to contribute to Tuveson’s research has been a gift, Glauber says. “Information from the investigations into my organoid are seriously being considered by my treating oncologists, even though I’m not in an official clinical trial,” she says. “I’m so grateful that researchers like Tuveson are making advances in the way pancreatic cancer may be treated. Their research will go a long way to personalize care and ensure that patients are getting the right treatment for them, not just the standard of care.”

Tuveson and colleagues are now designing a protocol for a research study that would recruit locally, in the New York tri-state area. The eventual hope, he says, is to take the method wide in a clinical trial. “We’re looking for a better scientific approach to pancreatic cancer,” he explains, “which will help us come up with better, individualized treatments for patients.”

To find out more about the organoid story, visit the Tuveson Lab website.