Early Study Shows Exercise Alone Can Reduce Inflammation

The link between obesity and cancer is very clear.

Ongoing research shows excess body fat will increase the risk of several cancers, including pancreatic cancer. But what is not yet clear is exactly how this extra body fat increases the risk of cancer.

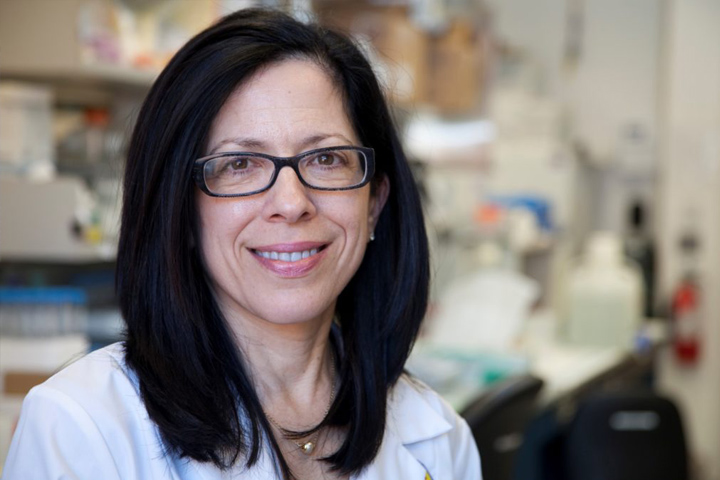

Cell biologist Zobeida Cruz-Monserrate, Ph.D., wants to find answers. In a May 2024 study published in the journal Cancer Research, she and her colleagues show that physical activity, with or without diet-induced weight loss, reduced inflammation in mouse models with genetically-induced pancreatic cancer. The mice were allowed to exercise voluntarily after gaining some weight through eating a high-fat diet. This reduction in inflammation among the mice slowed the cell processes involved in pancreatic cancer development and progression.

“We are research scientists and don’t see patients, but all of our research is patient-centered, which means we are focused on how can we improve human lives,” says Cruz-Monserrate. “Obesity is a real issue in cancer and I don’t know about you, but when somebody tells me to exercise it’s the last thing I want to do. So, we purposefully designed the (preclinical) study so that exercise was voluntary.”

Obesity and Inflammation

So-called chronic inflammation can be caused by many things, including abnormal immune reactions, a persistent infection, and obesity. Fat cells produce hormones called adipokines that can stimulate or inhibit cell growth. For example, the level of an adipokine called leptin in the blood increases with increasing body fat, and high levels of leptin can promote aberrant cell proliferation. Another adipokine, adiponectin, is less abundant in people with obesity than in people with a healthy weight and may have antiproliferative effects that protect against tumor growth.

Early in her academic career, Cruz-Monserrate had the opportunity to shadow a surgeon who was performing a Whipple procedure on a pancreatic cancer patient. “I’m a cell biologist but I wanted to see what patients have to go through,” says Cruz-Monserrate, a cancer researcher at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (Columbus). “Today, surgery is still the only potentially curative approach to pancreatic cancer. And I was determined to help people by studying this disease. I want to prevent it altogether.”

In her laboratory, she and her colleagues are studying the prevention of obesity-associated tumor development. The goal is to better understand molecular mechanisms that could be targeted to prevent tumor development. In an effort to discover alternative methods of studying obesity and its relationship to pancreatic cancer development, she uses preclinical models of diet-induced obesity that resemble obesity-associated pancreatic cancer. She does this to study some of the mechanisms that link obesity and pancreatic cancer initiation and progression. “People need to see the scientific data behind the link between obesity and cancer,” Cruz-Monserrate explains. “I especially think of high-risk populations like those who have a family history or pancreatitis,” she adds.

The researchers wanted to see if exercise was enough to forestall disease or whether both diet-induced weight loss and exercise are necessary. “The results are very interesting,” Cruz-Monserrate notes. “Pancreatic cancer is such a complex disease, and among high-risk populations, finding out if exercise and/or weight loss could boost existing and future therapies would absolutely help people. It would be complementary to treatment.”

About the Study

In this study, the researchers wanted to examine whether decreasing obesity through physical activity and/or dietary changes could decrease inflammation in humans and prevent obesity-associated pancreatic cancer in mice. They compared circulating inflammatory-associated cytokines (the signaling proteins that help control inflammation) in subjects that were overweight and obese. This was done both before and after a physical activity intervention which showed that physical activity lowered systemic inflammatory cytokines. Mice with KRAS G12D expression (associated with pancreatic cancer) were exposed to physical activity and/or dietary interventions during and after obesity-associated cancer initiation.

The researchers found that in mice with diet-induced obesity and KRAS G12D expression, the physical activity intervention led to lower weight gain, suppressed systemic inflammation, delayed tumor progression, and decreased pro-inflammatory signals in the adipose (fat) tissue. The benefits were not as evident when obesity preceded pancreatic KRAS G12D expression. This was a surprising finding and something that needs further exploration.

When the researchers combined physical activity with diet-induced weight loss there was delayed obesity-associated pancreatic cancer progression in the genetically-engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer. “But neither physical activity alone nor combined with diet-induced weight loss or chemotherapy prevented pancreatic cancer tumor growth when non-genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer were utilized regardless of obesity status, suggesting that when testing such interventions the preclinical model utilized does matter,” the researchers note. Moreover, physical activity led to an upregulation of IL-15ra in adipose tissue. However, this overexpression of IL-15/IL-15ra pathway in the adipose tissue slowed tumor growth only in non-obese mice.

The researchers say the study suggests that physical activity by itself or combined with diet-induced weight loss can reduce inflammation. That reduction in inflammation can then cause delays in developing pancreatic cancer and delay the progression of the disease.

“What we’re doing could help in prevention, survival outcomes, and quality of life,” says Cruz-Monserrate. But she stresses the science needs to be validated. “That’s the translational aspect of this work. Mice are not humans so we need people who are at high risk of pancreatic cancer or who are obese, and then to follow them prospectively. We need to see how obesity management strategies like diet, exercise, and/or obesity-targeted medication work overtime to prevent cancer. That’s the long-term goal.”