Pancreatic Cancer, Diabetes, and Endocrine Health: What You Need to Know

Diabetes and pancreatic cancer often go hand in hand, due to the pancreas’ role as the body’s insulin factory.

But did you know that pancreatic cancer treatment itself can influence blood sugar levels? Or that a damaged pancreas can exacerbate existing diabetes, or lead to an underrecognized form, Type 3c?

For these reasons—and more—Afreen Shariff, M.D., director of the Duke Endo-Oncology Program, Durham, North Carolina, and the co-founder of a virtual cancer support clinic called Citrus Oncology, believes every individual with pancreatic cancer should have an endocrinologist on their treatment team.

Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation, and surgery can alter how your body produces or responds to insulin. The treatments can also damage thyroid and adrenal glands, which manage important hormones that help the body function. Keeping these and other endocrine functions in check can be a game changer during cancer treatment.

“If you’re not feeling well during cancer treatment with symptoms like new or worsening fatigue, increased urination, thirst, and unanticipated weight loss, aberrant blood sugar levels could be contributing,” Shariff says. Cancer treatment may need to be held to allow time to manage high blood sugars and this could prove to be very detrimental to the success of the treatment, or lead to more toxic therapies later, she explains.

When Diabetes Is More Than Just Diabetes

The pancreas is the factory that makes insulin, and it is the organ that drives when and if diabetes occurs. When you eat, insulin is released to move the resulting sugar around the body to where it is needed, or where it is stored for later use. If the pancreas is occupied by cancer and unable to make enough insulin, the sugar is not moved around and stays in the blood, causing blood sugar levels to rise.

In individuals with preexisting diabetes, worsening control can be an early sign of pancreatic cancer. Unfortunately, it can also be easily missed or dismissed in others when it is new onset diabetes since diabetes is a common diagnosis. An estimated one-third of the U.S. population is considered prediabetic and prone to high blood sugar levels.

High sugar levels don’t always make you feel bad (a blood sugar level of 200 mg/dL is considered high, but most people can tolerate up to 500 mg/dL before feeling it), and the symptoms can be subtle. Unfortunately, this can hinder identification of how bad the situation is, Shariff explains.

If you notice rapid weight loss accompanied by blurred vision, nausea, cramps, feeling full without eating much, or other gastrointestinal symptoms, this is not normal and should be investigated further, she advises.

What to Be Aware of During and After Treatment

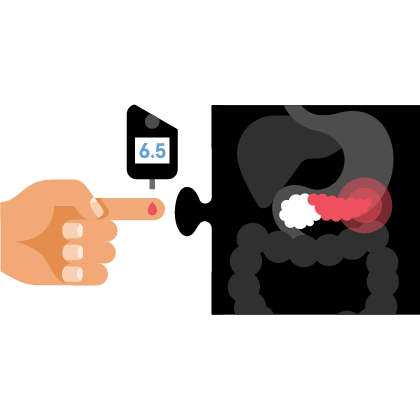

Cancer treatment regimens can wreak havoc on your endocrine system, not only because of the cancer-killing therapies, but also because of the steroids that often accompany them.

Many cancer treatments include intermittent steroid applications every few weeks. Blood sugar levels can spike during that time—someone with a base level of 150 mg/dL could see their levels go up to 300-400 mg/dL, Shariff notes.

Awareness and preparedness can go a long way towards mitigating the situation, and an endocrinologist can suggest adjustments to diet, pancreatic enzymes, and medications to treat high blood sugars during this time. Patients may require a combination of short- and long-acting insulin injections for a few days, for instance.

Changes to your body’s ability to produce and maintain insulin levels may continue after treatment, too.

Damage to the pancreas can cause something called pancreatogenic diabetes (also known as Type 3c diabetes). Often underdiagnosed, this type of diabetes is different to the more typical Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is caused by an immune attack that results in insulin deficiency and Type 2 diabetes results in insulin resistance. Type 3c is similar to Type 1 diabetes, where there is insulin deficiency. When patients receive steroids as part of their cancer treatments, they end up insulin resistant, similar to Type 2 diabetes, making Type 3c a unique challenge.

As such, its treatment is also a bit different, and more nuanced, Shariff explains. “Your treatment needs may change over time if your pancreas becomes more damaged.”

Post-treatment, patients should have tests to determine how much insulin their body is producing, and adjust accordingly. Pancreatic cancer patients who had Type 2 diabetes controlled with oral medications like Metformin before treatment might need to add insulin to their care plan afterwards, for example.

Managing Existing and Treatment-induced Diabetes Is Critical

Diabetes is a complex condition, so its management involves several strategies. In addition, diabetes affects everyone differently, so management plans are highly individualized.

Ideally, pancreatic cancer patients would be able to access an endocrinologist that can also think like an oncologist, anticipating the changes in appetite, energy, and blood sugar that might accompany different stages of cancer treatment and adjust diet, exercise, and medication plans accordingly.

Oncoendocrinology (also used interchangeably with endocrine-oncology or endo-oncology) is an emerging field at the interface of oncology and endocrinology that specializes in caring for cancer patients living with pre-existing or new endocrine diseases, from diabetes to pituitary dysfunction, steroid-induced hyperglycemia, or drug-induced thyroid abnormalities.

“Diabetes care is a great case study of a disease that can be treated remotely,” Shariff says. “We deal with numbers, such as A1C levels, blood sugar data collected through continuous glucose monitoring devices, which are easy to obtain. As long as we have access to the data, everything can be done remotely.” Because of this, even if specialist oncoendocrinologists are not available at every treatment center, virtual consultations can often be arranged.