Compassionate Use: An Option Beyond Standard of Care

In the world of pancreatic cancer, time is the patient’s most precious commodity. Delays in treatment—for whatever reason—can have life-threatening consequences.

Several factors make pancreatic cancer a challenge for doctors to treat—perhaps the most obvious being that pancreatic cancer is often not caught until the later stages. By that time, patients will likely not respond, or will stop responding, to the few treatment options available.

Doctors then face the dilemma of few options to offer their patients hope when the future looks grim. In these cases, “compassionate use”—treating with drugs (or medical devices) different from the standard of care—can bring hope to an otherwise dark situation. Compassionate use (or “expanded access”) describes the use of medications that are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) but are currently being studied in clinical trials; such medications are known as investigational drugs.

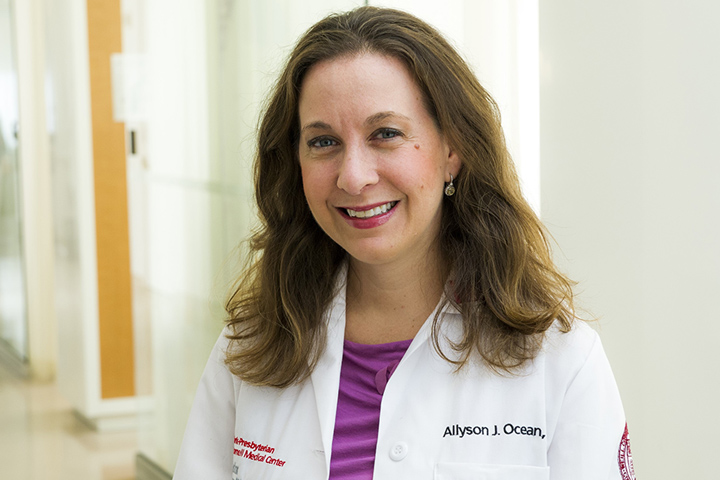

“Whenever there’s a disease that requires medical treatment, there’s a standard of care considered to be the most effective treatment to date,” says Allyson Ocean, M.D., a medical oncologist, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, and co-founder of Let’s Win Pancreatic Cancer. “These are drugs and regimens that became standards of care because they went through the rigors of clinical trials and have the data to support the safety and efficacy.”

Ocean explains that clinical trials also include standards of care, as studies often compare the standard drugs to other treatments. This holds true for phase III clinical trials. In those trials, the new regimen is usually compared to the standard of care or included with the standard to see if the new drug works better than what is already in use.

Off-Label Compassionate Use

Compassionate use comes into play when trying to help the patient live longer. Take the drug trastuzumab (Herceptin), for example. Commonly used to treat breast and stomach cancers, the FDA has not approved the drug for pancreatic cancer. However, a doctor may use trastuzumab in a patient with pancreatic cancer who has received several other pancreatic cancer treatments if their tumor contains the protein that trastuzumab is targeting. The practice of using drugs to treat a condition other than the one for which they are FDA-approved is known as off-label compassionate use. Even though trastuzumab is not indicated for pancreatic cancer, the rationale is that the drug may help that pancreatic cancer patient live a little bit longer. So having other treatment options helps.

Qualifying for Compassionate Care

But not every patient with pancreatic cancer can receive compassionate care. Each patient must meet certain criteria. First, they must have either stopped responding to the standard of care and other common treatments. Secondly, they must be healthy enough to withstand the treatment. In other words, they cannot be bedridden and must be able to move around out of the bed at least half the day. However, checking these two boxes does not guarantee they can receive the additional treatment. Access is also an issue.

Let’s take the case of off-label drugs. In the world of pancreatic cancer, accessing an off-label drug for compassionate use is not easy. In many cases, insurance companies will not pay for cancer drugs prescribed off-label, leaving patients to foot the bill. Unfortunately, most patients cannot afford expensive treatments. And the trouble doesn’t stop there.

When it comes to experimental treatments used compassionately in pancreatic cancer, doctors have to request permission from the FDA and the drug’s manufacturer to use the drug for their patients. Ocean finds that drug companies are generally helpful, with some going so far as to fill out the forms to be submitted to the FDA. However, the real monkey wrench in the process is waiting on a response (and, hopefully, approval) from the FDA. Responses can take weeks or months. Even then, the outcome may not be in the patient’s favor.

“Sometimes the FDA doesn’t realize the sense of urgency in pancreatic cancer,” Ocean explains. “If you don’t get approval, it’s usually because there’s not enough evidence. Some treatments do work even though there is little published data.”

Getting FDA approval becomes even more challenging when seeking clearance—the word used to describe approval—to use a medical device. This is because medical devices have a different set of criteria for approval, and the way they work may be a bit more difficult to understand because the device is novel and unlike anything already out there.

According to Ocean, one strategy to increase the chances of getting a green light from the FDA is to match the treatment as closely to the patient as possible. If the FDA approves a treatment, they require the doctors to follow their patients and periodically report their patients’ progress. To increase their chances of accessing compassionate use, Ocean recommends that patients and their loved ones actively seek out clinicians who think outside the box. She also encourages patients to switch doctors if they feel their needs are not being met.

Compassionate Use vs. Clinical Trials

Clinical trials offer another option to get treatment—especially for patients for whom cost may be an issue. But getting enrolled comes with its own hurdles because each trial has qualification criteria. “You have to have a clinician who is willing to find the appropriate clinical trial for you,” Ocean says.