This Versus That: Words to Know

The cancer dictionary is extensive and complex.

Just when you think you have a handle on the lingo, you learn a new term that requires decoding. To complicate matters, many words in the oncology world are related, but different. Here’s your go-to guide to “related but different” words to know in the pancreatic cancer space.

Germline Mutation Versus Somatic Mutation

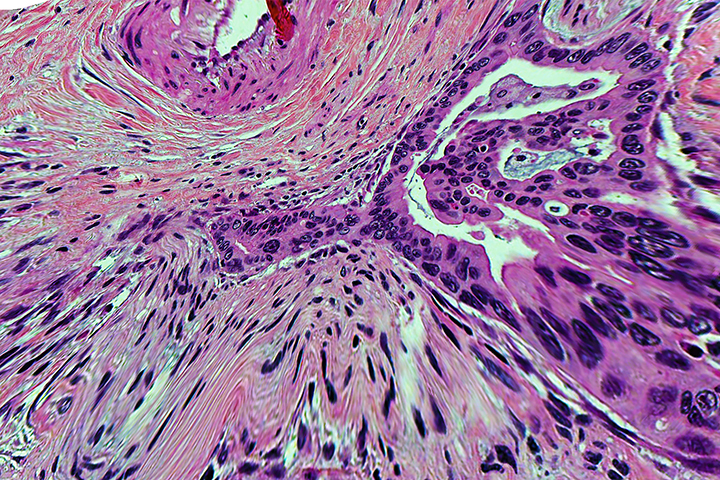

Cancer occurs as a result of genetic mutations, or when harmful changes alter a DNA sequence. Cancer-causing mutations come in a variety of different categories based on the tissue where they occur. Two of the best known: germline mutations and somatic mutations.

Germline mutations: A germline mutation is a genetic change that occurs in a sperm cell or an egg cell, and is passed directly from a parent to a child at the time of conception. These germline mutations are copied into every cell of the body, including the reproductive cells, and can pass from generation to generation. Cancers that arise from a germline mutation (about 5 to 10 percent of all cancers) are also called inherited or hereditary cancers.

Somatic mutations: Somatic mutations (also called acquired mutations) account for about 75 to 80 percent of all cancers. They arise from damage to genes in an individual cell. These mutations are not passed down from parent to child, but rather occur during a person’s life,because of random errors in DNA as cells divide. Toxic exposures, tobacco, ultraviolet radiation, viruses, and simple aging can all lead to somatic mutations.

A side note: There’s also something called familial cancers, a term used to describe cancers that are not caused by a germline mutation but do tend to cluster within families.

Genetic Testing Versus Molecular Profiling

Genetic testing and molecular profiling are both standard of care for pancreatic cancer patients. The results not only help doctors diagnose the type and stage of cancer, but they can also help inform treatment decisions. Whenever possible, pancreatic cancer patients should receive both types of testing.

Genetic testing: Most of us know about genetic testing because of the popularity of at-home kits that provide information about your family heritage. But medical genetic testing is important for cancer patients. It allows doctors to pinpoint specific mutations in your genetic information. This genetic information includes a combination of genes, DNA, and chromosomes, all of which govern how your body grows and functions. While each person has a unique set of genetic changes, some of these changes affect your propensity for developing cancer, among other diseases.

Molecular profiling: Molecular profiling focuses on the tumor, not the person. This form of testing examines the DNA of cancer cells to offer a sort of blueprint of genetic mutations and biomarkers inside a tumor. With molecular profiling, doctors can identify and target these unique differences inside the tumor to help improve outcomes.

Radiation Oncology Versus Surgical Oncology

Oncology is an umbrella term for the study of cancer, so a physician who oversees cancer treatment is called an oncologist. If you have pancreatic cancer, chances are good that you’ll work with a surgical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, or both. Some oncologists focus solely on particular cancer types or treatments. Others are dedicated to a particular specialty, such as surgery and radiation.

Radiation oncology: Radiation oncology focuses on treating cancer with radiation therapy. With radiation, doctors use high-energy beams to shrink or destroy cancer cells. The beams create small breaks in the DNA of cancer cells to prevent them from growing and dividing. When treating pancreatic cancer, doctors often use radiation not to cure the disease, but to control the growth of the cancer, relieve symptoms, and enhance patients’ quality of life.

Surgical oncology: A surgical oncologist is a physician who specializes in performing biopsies and removing cancerous tumors. With pancreatic cancer, surgical oncologists often perform surgery called a Whipple procedure to remove the head of the pancreas and sometimes the body of the pancreas and parts of the stomach, too.

A side note: There’s also something called integrative oncology, where trained specialists use complementary therapies, such as reiki, acupuncture, and high-dose vitamin C, alongside surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Integrative therapies can help achieve treatment goals, manage side effects, and improve quality of life for cancer patients; they can be especially helpful for pancreatic cancer patients since conventional treatment options are limited.

Palliative Care Versus Hospice

Hospice and palliative care are often used interchangeably in conversation. Both provide compassionate care to patients who are navigating life-limiting illnesses, but they’re actually quite different.

Palliative care: Also called supportive care, palliative care focuses on relieving pain and enhancing comfort in patients who are suffering from serious illness. With palliative care, the patient may not be at the end of life; they may just need comfort measures while receiving active treatment.

Hospice: Hospice care always includes palliative care, but it also addresses the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of patients who are expected to die within six months. While a small subset of patients do come off hospice, this type of care is reserved for terminal patients who are no longer undergoing curative treatment.

Cachexia Versus Anorexia

Cancer alters the body’s metabolism, which may lead to unexpected weight changes. Add grueling treatment regimens, nausea, and taste disturbances to the mix, and it’s a safe bet that cancer patients will lose weight during treatment. Cachexia, anorexia, and treatment-associated weight loss are all related, but they’re also very different.

Anorexia: People often associate the word “anorexia” with the eating disorder, anorexia nervosa. In cancer patients, doctors use the word “anorexia” to describe an extreme aversion to food. Anorexia-associated food aversions and weight loss can stem from the disease itself (cancers can secrete inflammatory proteins that impact the body’s metabolism), or as a side effect of treatment.

Cachexia: Cachexia, or wasting, is most common among patients who have advanced cancer. It’s a serious and life-threatening condition marked by significant muscle loss, appetite changes, weight loss, and general fatigue and weakness. When patients are literally starving, they lose fat first, then muscle.

A side note: Most patients experience a certain degree of weight loss during and after treatment. While weight loss can be a side effect of chemotherapy and even radiation, it’s also a product of cancer-caused anorexia.

Still encountering cancer terms that are seemingly indistinguishable? It’s important to ask your doctor and healthcare providers to explain the distinctions between related terms—and in language that’s easy to understand. “Cancer is complicated,” says Dr. Allyson Ocean, a medical oncologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. “Our job is to make the road easier to navigate.”