Pancreatic Cancer Pathology: How Doctors Get to a Diagnosis

One of the most important members of a cancer patient’s medical team is someone they may never meet: the pathologist.

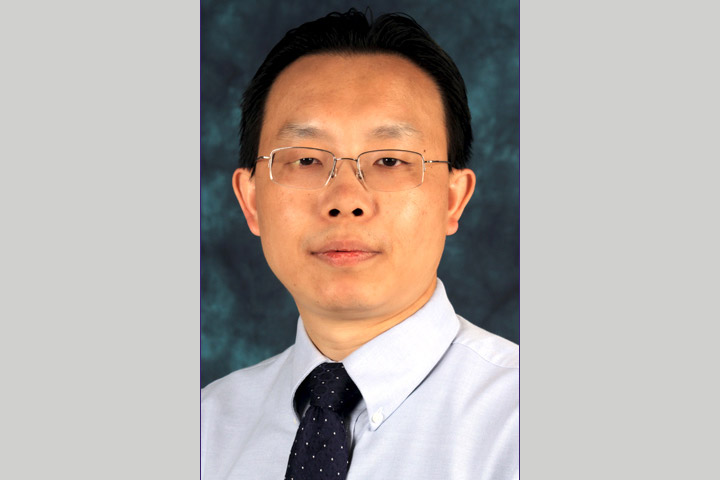

What exactly is it that pathologists do? “Pathologists are doctors who work in the laboratory, analyzing data that provides test results and interpreting and diagnosing the changes caused by disease in tissues and/or body fluids, which ultimately provide the basis for the treatment decisions of surgeons, oncologists, and radiation oncologists,” said Jingxin Qiu, M.D., Ph.D., Professor of Oncology and Director of the Clinical Immunohistochemistry Laboratory at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York.

Pathologist Training

Pathologists receive very focused training. In addition to completing a medical degree, they undertake residencies, which typically last four years and include training in clinical or anatomical pathology, as well as instruction in image analysis, cytogenetics, molecular diagnostics, and protein biochemistry. This is followed by one- or two-year fellowships focused on their subspecialties.

While a primary care doctor or oncologist is the one likely to deliver the diagnosis, a pathologist works behind the scenes to develop it, determining whether the patient has cancer and what exactly doctors will be dealing with.

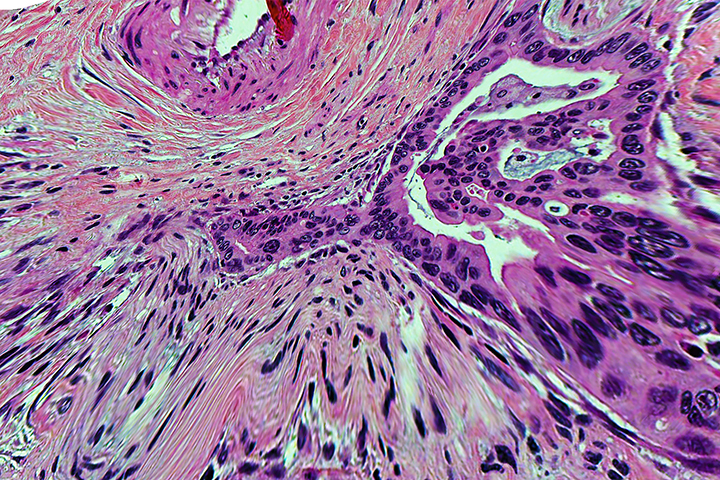

Typically, the diagnostic process begins with an endoscopic biopsy, where a thin flexible hollow tube is inserted into the abdomen to remove a small amount of tissue and/or fluid from the pancreas. This tissue is sent to pathology, where the process includes fixing and embedding the sample into paraffin wax. It is then cut into extremely thin slices, placed on glass slides, and stained so that it can be viewed clearly under a microscope. The pathologist will review the biopsy to determine if tumor cells are present and, if they are, determine the type of tumor. Ideally, any pancreatic cancer diagnosis should be reviewed by pathologists who specialize in pancreatic cancers, Qiu explains.

“Having the correct pathological diagnosis is the most important first step that determines the management of pancreatic cancer patients,” he adds.

In the era of precision medicine, pathologists serve an additional crucial purpose: they test cancer cells’ biomarkers to determine whether or not the patient might be a good candidate for targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or other emerging treatments.

In addition to diagnostic reports, pathologists also prepare post-surgical reports. These reports will describe the removed tumor, as well as the characteristics of any remaining cancer. They can also provide additional information such as whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes or to distant sites, such as the liver (metastasis).

Making Sense of Pathology Reports

Gross? Microscopic? Margin? Mitotic rate? Like many medical texts, pathology reports can be confusing. Think of a pathology report as a cancer profile. It provides important details about the location and extent of the tumor.

Typical information included in the report:

- Gross description: Describes the tissue sample without using a microscope, such as size (largest dimension of the tumor, as measured in centimeters), shape, color, weight, and what it feels like.

- Microscopic description: Describes what the cancer cells look like when stained and observed under a microscope, how they compare to normal cells, and whether they’ve spread into nearby tissue.

- Diagnosis: The pathologist will weigh all of these findings and make a diagnosis. It will usually contain the type of cancer, tumor grade, lymph node status, margin status, and stage.

- Histology: The subtype of pancreatic cancer, such as adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, hepatoid carcinoma, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), pancreatoblastoma, carcinoid tumor, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor, gangliocytic paraganglioma, among other types.

- Grade: The pathologist compares the cancer cells to healthy cells. A tumor grade reflects how likely it is to grow and spread.

○ Grade 1: Low grade, or well-differentiated. The cells look a little different than regular cells. They aren’t growing quickly.

○ Grade 2: Moderate grade, or moderately differentiated. They don’t look like normal cells. They’re growing faster than normal.

○ Grade 3: High grade, or poorly differentiated. The cells look very different than normal cells. They’re growing or spreading fast.

○ Invasive or noninvasive: Noninvasive, or “in situ,” cancers stay in one specific part of the body. Cancers that spread are called invasive. Metastatic cancer is when the disease spreads to another part of the body from where it started. - Tumor margin: In post-surgery samples, the margin refers to an extra area of normal tissue surrounding the tumor which was removed during surgery. The pathologist will study this area to see if it’s free of cancer cells.

○ Positive: Cancer cells are found at the margin. This may mean that potentially more surgery is needed.

○ Negative: The margins don’t contain cancerous cells. - Lymph nodes: Your lymph nodes are small organs that are part of your immune system. Your doctor may biopsy nearby lymph nodes to see if the cancer has spread. They’re positive if they have cancer and negative if they don’t.

- Mitotic rate: A measure of how quickly cancerous cells are dividing, usually calculated by counting the number of dividing cells in a certain amount of tissue.

- Cancer stage: Cancer staging helps your doctor decide what treatments will work best. Most cancers are staged with a Roman numeral I-IV (1 to 4) based on where it is and how big it is, how far it has spread, and other findings. The higher the stage, the more advanced the cancer. Some cancers have a stage 0, which means it’s an early-stage cancer that has not spread.

- Comment: If your cancer is tricky to diagnose, the pathologist may write extra comments. They can explain the issue and recommend additional tests.

Staging Details

The pathological staging classification uses the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM system, which has three criteria to judge the stage of the cancer: the size and location of the primary tumor (T), the adjacent lymph nodes (N), and whether the tumor has spread to the rest of the body (M).

TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed.

T0: No evidence of primary tumor has been found.

Tis: Carcinoma in situ.

T1: The tumor is 2 cm or less in greatest dimension.

T1a: The tumor is 0.5 cm or less in greatest dimension.

T1b: The tumor is more than 0.5 cm and less than 1 cm in greatest dimension.

T1c: The tumor is 1-2 cm in greatest dimension.

T2: The tumor is between 2 cm and 4 cm in greatest dimension.

T3: The tumor is more than 4 cm in greatest dimension.

T4: The tumor involves the celiac axis, or the superior mesenteric artery, and/or common hepatic artery, regardless of size.

Nx: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed.

N0: No regional lymph node metastasis has been found.

N1: Regional lymph node metastasis has been found in 1 to 3 lymph nodes.

N2: Regional lymph node metastasis has been found in 4 or more lymph nodes.

M0: No distant metastasis has been found.

M1: Distant metastasis has been found.

And There’s More

The pathologist may perform additional tests to get more information about the tumor that cannot be determined by looking at the tissue with routine stains under a microscope.

- Immunohistochemical stains: IHC uses antibodies to identify specific antigens of cancer cells. It can be used to determine where the cancer started and distinguish among different cancer types.

- Flow cytometry: A method of measuring properties of cells in a sample, including the number of cells, percentage of live cells, cell size and shape, and presence of tumor markers on the cell surface. Tumor markers are substances produced by tumor cells or by other cells in the body in response to cancer or certain noncancerous conditions.

- Cytogenetics: Tissue culture and specialized techniques are used to provide genetic information about cells, particularly genetic alterations. Some genetic alterations are markers or indicators of a specific cancer. Some alterations can provide information about prognosis, which helps the doctor make treatment recommendations. Tests include fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), real-time PCR or quantitative PCR, reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), Southern blot hybridization or Western blot hybridization. For more information on these tests, check out this National Cancer Institute site.

Still confused by the technical medical language and jargon? Ask your doctor! And if you are still not satisfied or want a second opinion, contact GI/liver/pancreas subspecialty pathologists to discuss your report, Qiu advises.

For more information watch the video from Roswell Park about pathology.