RASolute 302 Trial for KRAS and Other RAS Mutations Recruiting at Multiple Sites

Finding ways to target KRAS mutations, found in up to 90 percent of pancreatic cancer patients, has been the focus of numerous research efforts for years.

Oncogenes are genes involved in cell growth and division that, when mutated, can change healthy cells into cancer cells. RAS is the most common oncogene and KRAS is a specific type of RAS oncogene. RAS was once considered “undruggable” due to its unusually smooth structure that makes it difficult for small molecules to bind to its surface. In addition, many cancer-causing mutations in RAS result in proteins that are constantly active. Or, put more simply, they are locked in an “on” state, dubbed RAS(ON). And it’s been challenging to develop drugs that can shut them off.

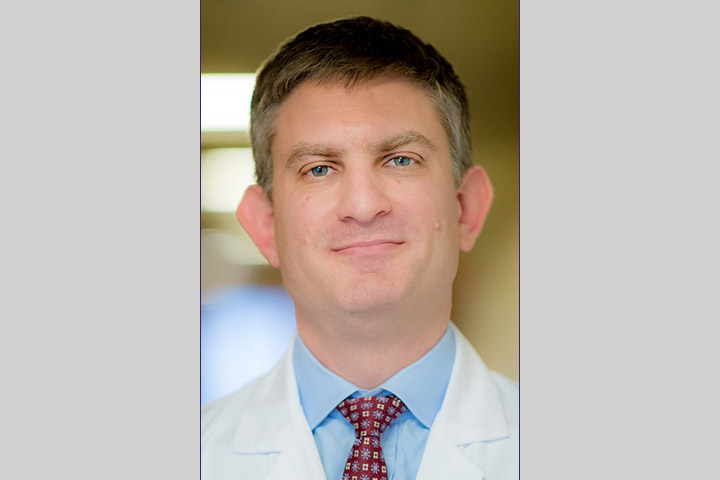

But that was then. Continued research proved RAS was indeed “druggable,” and today there are two approved RAS inhibitors and several more being tested. “We used to think that targeting RAS was impossible, yet we knew that if you could target RAS, and potentially shut it down, patient treatment, especially in pancreatic cancer, would be greatly expanded,” says Hani Babiker, M.D., a principal investigator on a trial called RASolute 302, which compares a RAS(ON) inhibitor to standard-of-care chemotherapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer.

A Pan-RAS Inhibitor Takes Center Stage

The phase III trial, sponsored by Revolution Medicines, focuses on a drug called daraxonrasib. The drug is what scientists call a “molecular glue,” which is designed to target and disrupt the function of the RAS protein. It is a pan-RAS inhibitor, able to target multiple RAS isoforms, including mutations like G12X, G13X, and Q61X as well as targets like G12C, G12D, and wild-type KRAS.

Daraxonrasib works by forming what is called a “ternary complex” among RAS, a protein called cyclophilin A, and the molecular glue itself, which blocks the binding of RAS to its downstream target, RAF, an important part of a signaling pathway called MAPK, explains Babiker; he is a physician– scientist and a hepatopancreaticobiliary leader at the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center, in Jacksonville, Florida.

A ternary complex refers to a three-component complex formed when a molecular glue binds to two protein partners, “effectively creating a new interaction or stabilizing an existing one,” he adds. This binding process induces a new protein-protein interaction that wouldn’t otherwise occur, or enhances an existing one.

RAS proteins regulate cell growth by switching between “ON” and “OFF.” When you’re healthy, RAS is mostly turned OFF, and is only transiently switched ON in response to certain growth signals. But cancer-causing mutations disrupt this delicate balance. The result is a shift from RAS being mostly OFF to predominantly ON..

Tumors like those in pancreatic cancer rely on continued oncogenic RAS(ON) signaling for survival. “But once you disrupt the RAS signaling pathway you conceivably inhibit tumor growth,” Babiker says. “That’s what makes this trial exciting. We went from not being able to target RAS at all to now being able to target the active form of RAS proteins, not just KRAS G12C. It has the potential to help pancreatic cancer patients, as well as those with other cancer types like non-small-cell lung cancer.”

Early Research Showed Clinical Activity

Early research looks promising. A phase I/Ib open-label trial of the best-tolerated dose, as well as the safety and effectiveness, studied treatment with daraxonrasib (formerly called RMC-6236) in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring RAS mutations or wild-type RAS. As of the July 23, 2024, data cutoff date, a total of 127 patients previously treated for pancreatic cancer were treated with daraxonrasib at doses ranging from 160 mg to 300 mg once daily.

Patients with pancreatic cancer whose initial treatment was not effective (i.e. in second-line treatment) and who harbored a KRAS G12X mutation had a median progression-free survival of 8.5 months and a median overall survival of 14.5 months. Similar patients with any RAS mutation had a median progression-free survival of 7.6 months and a median overall survival of 14.5 months.

Landmark overall survival for these patients at six months was 89 percent and 91 percent in patients with pancreatic cancer harboring a KRAS G12X mutation and patients with pancreatic cancer harboring any RAS mutation, respectively. The objective response rate for patients with tumors harboring KRAS G12X mutations was 29 percent in the second-line group and 22 percent in the third-line (two treatments no longer effective) and beyond group. The disease control rate was 91 percent and 89 percent in these patients, respectively. No new safety signals were observed.

“Patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer need more options, so these results showing significant clinical activity along with a good safety profile certainly do provide some hope,” Babiker notes. “Plus, this drug is oral form meaning patients just take a pill, and that’s a real plus. But I think the most important thing is this kind of activity supports the ongoing phase III trial. It shows promise but we have to wait for the data.”

About the New RASolute 302 Trial

In the phase III randomized trial, daraxonrasib will be compared to standard-of-care chemotherapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer who were previously treated with one prior line of therapy, with either a 5-fluorouracil-based or gemcitabine-based regimen.

Patients will be randomly assigned to either receive daraxonrasib (Arm A) or the investigator’s choice of standard-of-care chemotherapy (Arm B). The investigators are looking at progression free survival and overall survival in the RAS G12-mutant population.

The study is available at numerous sites in the United States (including Puerto Rico), and is also recruiting in France, Italy, and Spain. Investigators hope to recruit some 400 participants.

“This is an important study since there is the potential to expand treatment options for a patient population that desperately needs more effective treatment options,” Babiker says. “The study group of about 400 patients will provide very robust data. I’m hopeful about this trial, but I’ll be really excited by positive data because that could be a game-changer for many patients.”

Researchers are also developing a trial focusing on daraxonrasib as a first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

We encourage you to consult your physicians for clinical trials that may be right for you. The website ClinicalTrials.gov provides more details about this trial as well as many others. You can visit the Let’s Win Trial Finder for a list of all active pancreatic cancer clinical trials.