What You Should Know About Pancreatic Cysts

Discovering you have a pancreatic cyst—or multiple cysts—can be scary. But it is not necessarily devastating news, and it does not mean you have pancreatic cancer.

In fact, pancreatic cysts, particularly among people over age 50, are an increasingly common finding. “We’re in an era where almost anyone who complains of abdominal pain is going to get a scan. And our scanners are getting better and better and they’re identifying smaller and smaller things,” says V. Raman Muthusamy, M.D., Director of Endoscopy at UCLA Health and Professor of Clinical Medicine at David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “Plus, we know that pancreatic cysts increase with age. Some studies suggest that one in 40 people have a pancreatic cyst by age 50. That number increases to one in four by age 70.”

Answering Your Questions

Just because pancreatic cysts are fairly common doesn’t mean they’re not concerning. Muthusamy answers your most pressing questions about pancreatic cysts and what they mean in terms of your future pancreatic cancer risk.

What is a pancreatic cyst?

Like a cyst in any other part of the body, pancreatic cysts are water- or mucus-filled structures. While some people are predisposed to develop pancreatic cysts because of genetics, most arise from inflammation of the pancreas (also called pancreatitis). In most cases, these cysts are benign.

How are pancreatic cysts typically identified?

Most cysts are discovered while patients are undergoing CT or MRI imaging for a different indication. Others are discovered when patients complain of abdominal pain, nausea, unexplained weight loss, or other gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

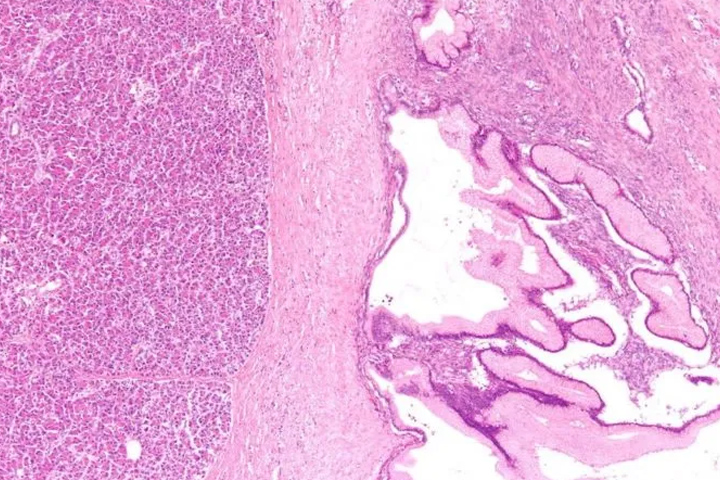

How do doctors differentiate a cyst that may cause some concern from one that’s harmless?

It’s not entirely clear, but there are some distinguishing factors:

- Size. Cysts that are more than 3 cm in size tend to be more aggressive.

- Solid components. Cysts that have a bump, nodule, or mass attached are more likely to be problematic.

- Fluid. If the main pancreatic duct, which secretes the pancreatic juice, dilates above a certain range, that can also be predictive of a more serious condition.

The problem is, all of these things can also be associated with pancreatitis. You can even get focal masses—a mass or lesion that develops at a circumscribed area of the organ—with chronic pancreatitis. So there’s a big degree of overlap between the characteristics of potentially premalignant cysts and inflammatory nonmalignant cysts.

Since there’s this overlap between potentially cancerous and noncancerous cysts, what are some tools GI specialists can use to determine whether a cyst is likely to develop into a cancer?

We can do endoscopic ultrasound, where we put a flexible scope through the mouth, down into the stomach so we can get a good view of the back wall of the stomach. We can draw samples of the pancreatic fluid and analyze it for biochemical markers such as CA 19-9 or carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which are predictive of cancer. We also have some novel approaches where we can take needle biopsies of the cyst wall to help better characterize the cyst.

How do the results of those tests impact care for these patients?

If the cyst has concerning features, current guidelines require advanced imaging tests for five years. If we can prove that a cyst is benign, we can provide the patient with some reassurance and sidestep the cost of additional imaging tests, which could amount to $15,000 to $25,000 over five years. So our goal is to provide reassurance to those who truly have a benign cyst, and also identify those who have potentially aggressive cysts early, before they can spread.

What advice do you have for patients who have been diagnosed with a pancreatic cyst?

First, take a deep breath. People tend to think the worst when they hear something about the pancreas. But pancreatic cysts are a very common finding—and most of these cysts do not turn into pancreatic cancer.

How are pancreatic cysts treated?

In most cases, pancreatic cysts require nothing more than continued observation and additional imaging. These cysts are often slow-growing, so we’re usually able to notice changes and remove them before they become cancerous. In a few cases, we may detect concerning features and recommend surgical removal. The good news is that outcomes for these patients are dramatically better than for solid pancreatic tumors, and we can usually remove the cysts with a minimally invasive approach.

Muthusamy advises that if you have symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, new onset diabetes that can’t otherwise be explained, you should talk to your doctor. And if you get a scan that shows an abnormality in the pancreas, follow up with your doctor and your physician to make sure you get a proper workup and to evaluate things further.