At the Table: How to Talk to your Family and Friends about Pancreatic Cancer

Let’s Win is introducing patients’ voices to our Managing Pancreatic Cancer section.

Patients and survivors will share useful information about how they managed their care during treatment, their experiences traveling after having Whipple surgery, why they have become advocates, and what they are doing to help others facing the same diagnosis.

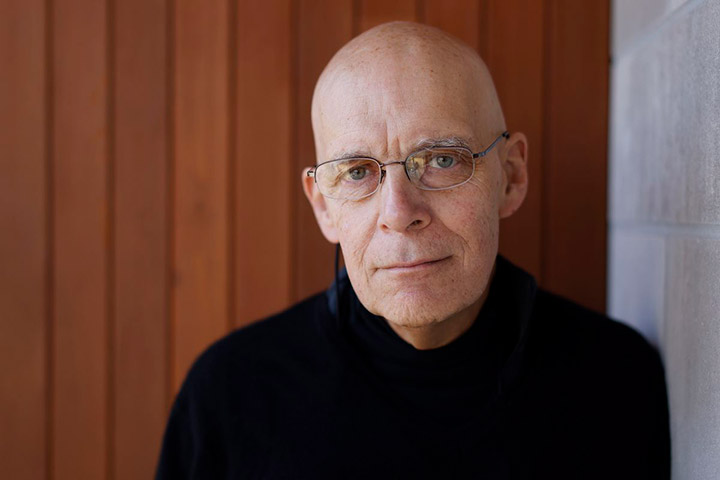

We will also convene an occasional roundtable, where we ask different people the same questions. Our first roundtable focuses on telling people about your diagnosis. At the table are David Dessert, a BRCA2-positive advocate; Miggie Olsson, a long-term survivor who volunteers with patients; and John Moisan, a five-year survivor and advocate.

How did you tell your family and friends that you have pancreatic cancer?

Everyone told their immediate family first, in person when they could, and over the phone when they could not. But as David Dessert says, once the diagnosis came, there was not a lot of control over the situation.

DD: I told work, friends, and family that they found something on my tumor that was consistent with cancer, but it’s not definite yet. My parents flew in immediately, before we even had a definite diagnosis. We were very straightforward and honest with my children—ages 13 and 16 at the time.

MO: With some of my friends I needed face-to-face contact, so that they could see that I was not dying, not even looking sick. I wanted each person to know that I was confident that I had a good chance, because I was with a first-class medical team that had the latest research.

I am not someone who can hide the truth from anyone. I wanted to give each person connected with me the time to process the information and possible outcomes. To be sure, a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is an emotional bit of news to pass on, but as difficult as it was, it helped me to know my family and friends knew what we were going through. I ended up with more support than I could have imagined.

JM: I came home from “the appointment” with my PCP and told my wife in person. We cried. I have five children and a couple of them panicked because they knew about pancreatic cancer. The other three had no idea of the seriousness of the disease.

DD: My children each processed the news in their own ways. They rarely asked me any questions about my disease or treatment, preferring to talk to their mother. But I always told them my truth.

I took my older son with me to the oncology appointment where I first asked about my life expectancy. The oncologist looked at me, then my son, then back at me and asked if I really wanted to discuss this now? “You bet,” I replied. I knew that opportunities to teach my children life lessons were dwindling and I felt it was important for him to see how his father faced death.

JM: I told some good friends that evening, because we had been invited to their house for dinner. Our friends were speechless. When I told a couple of other friends the next day, one was concerned, but the other indifferent. I live in a small town, so it was a matter of two days and almost everyone in town knew of the diagnosis. Some were ordering flowers for my funeral; others called or came over with words of encouragement.

DD: One co-worker I had worked closely with hardly spoke to me ever again which was somewhat disappointing. But I realized that his discomfort was more about how he was processing the news than anything I had done.

Is there anything you would do differently?

JM: I would rather have told my children in person, but that is impossible because they all live in different parts of America.

DD: Informing work can be a problem for many, but my relationship with the HR department was outstanding and they really looked out for me. In one instance, they helped me exercise a hidden benefit to convert my company life insurance policy to an external term-life policy, whose payments were covered for as long as I was disabled. In another, when our division was sold off and being shut down, my local HR department made sure I stayed on long-term disability instead of being laid off. Being on good personal terms with your company can work out to your advantage.

MO: I would have shaved my head when my hair started falling out. My husband didn’t want me to do that, because it would be obvious that I had cancer, so I just kept cutting it, even when my hair became very thin. I would much rather have been honest from the beginning.

Also, I would have contacted my medical team more often. I think I could have avoided many problems with side effects if I had talked with my team. Even though I was stage IV, I was strong going into treatment so I thought I was not as critical as other cancer patients and that I could handle side effects on my own. It’s interesting how irrational I could be, trying not to unnecessarily bother the medical team.

What would you NOT say or so, knowing what you know now?

DD: I would be more careful about what I share on social media. Even comments meant only for friends can betray you later. Not long after my Whipple surgery, my long-term disability insurer scoured the internet and found that I was riding my bicycle enough that they no longer considered me disabled. They cancelled my coverage. A few months later, my Social Security disability payments went away.

MO: There are two things I would not do. I would not bother trying to explain treatment specifics or medical minutiae to anyone. Very few people were able to process all that information without being overwhelmed.

I would not try to accommodate every person who wanted/needed my time. I’m a MOM and have always tried to take care of others, but I couldn’t control the emotions of others around the threat of death. I needed to conserve energy, stay involved in things that were important to ME, and let others take care of each other. So, I would recommend that people think carefully before saying “yes.”

JM: I would offer more words of encouragement. I was diagnosed in June 2014 and after Googling pancreatic cancer, some of my kids became despondent. They learned that the survival rate was 5 percent but had ZERO understanding of what the diagnosis was. I believe that they all thought I was destined to die.

My wife had a stroke in 2010 and I was (and remain) her caregiver. Our second oldest daughter said, “I can handle one sick parent but not two sick parents.” She cut off all communications with us for three years. Eventually I went to see her and had a long conversation. We are better now, but we are still more distant than we were before my diagnosis.

What are your suggestions for best ways to handle these difficult conversations?

MO: One-on-one direct contact, as in a phone call or face-to-face, worked best for me. A group email doesn’t give anyone the opportunity for an intimate exchange. I have found that one-on-one conversations give people a moment to cement a relationship, the opportunity to get valuable information, and possibly find out what each person can do for you. Everyone is so different in needs and skills. That personal contact was very important to me.

DD: Being honest has always worked for me. That does not mean I open up to anyone and everyone who asks for details, but with those with whom I do share, straightforward answers work well for me. If I don’t want to get into too many details, I just tell them that too.

JM: There is no way to handle these conversations, except to tell the truth and try to build HOPE that some people do survive. It’s important to get through the medical tests, biopsies, pathology, and give people accurate information related to the cancer and possible outcomes. The same information should be told to friends. I tell EVERYONE that will listen about my diagnosis, possibilities, and current status. I am VERY BOLD about talking about PANCREATIC CANCER, but I never use the words “cancer-free” or “the C word.”

DD: It’s been nine years since my diagnosis, and I think the most difficult conversation going forward would be telling my wife if there is ever a recurrence. Having had our future together tossed up into the air and being able to finally reclaim it, I shudder to think about going through that again. But I imagine that I’d be straight with her again.

Any other thoughts or suggestions?

DD: Advice given by others should only be considered if it matches you and your situation. We’re all unique and what works well for some will work poorly for others. Listen to the buffet of experiences and choose what fits you.

When I listen to others tell their stories, sometimes nothing about their experience resonates with me. But I realize that there is a reason they have chosen this story to share with me—I just haven’t seen it yet. My goal is to find that nugget they’re really trying to share because it’s often gold.

MO: Don’t let anyone else’s attitude or fears affect your attitude. Conversations can open up Pandora’s box, but you the patient can weather this with confidence in your medical team and by focusing on the positive things going on in your life. Don’t spend any time or energy trying to convert someone with a negative attitude. Your job is to take care of YOU and get through this.

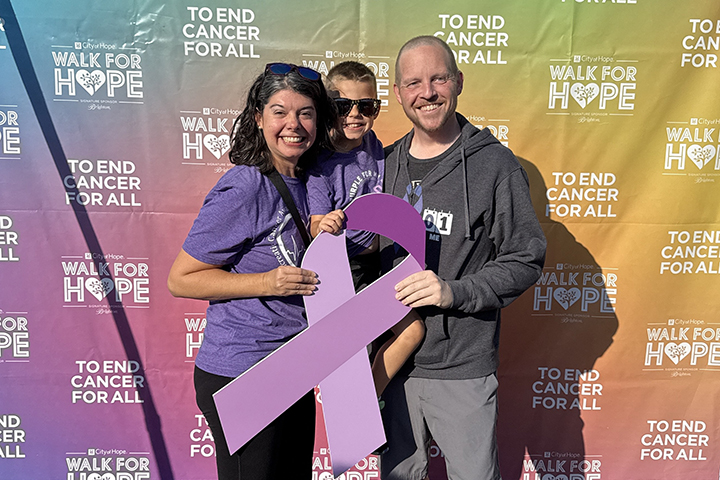

JM: Get your family and friends involved in pancreatic cancer awareness activities. All our kids participated in the PanCAN 5K PurpleStride event in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in June 2019, when I became a five-year survivor. Our daughter from South Carolina wore a shirt that said “I wear purple for my Dad.” She ran with me the entire distance of 3.1 miles in 42 minutes; I was the oldest person (age 72) to finish the event. Since 2014, I have organized an event at the South Dakota State Capitol Building called Light the Capitol Purple for Pancreatic Cancer Awareness. I do this to involve the community and my friends in pancreatic cancer awareness. In 2019, we broadcast the event live on the internet, where over 13,000 people viewed the ceremony worldwide.