Solving the Mystery of Cachexia

For many pancreatic cancer patients—and their families—one of the most difficult aspects of the disease is the metabolic disorder called cachexia.

Cachexia (pronounced kuh-KEK-see-uh) is characterized by extreme weight and muscle loss. It usually occurs in the end stage of a disease, and may affect as many as 80 percent of people with advanced cancer. Because the cause is metabolic, adding more food and calories to a person’s diet doesn’t change the course of the disorder. This leaves patients, caregivers, and family members frustrated and frightened.

“Patients feel guilty that they aren’t eating enough and caregivers feel guilty that maybe they aren’t feeding the person enough and what is already an extraordinarily difficult time becomes even harder,” explains Teresa Zimmers, Ph.D., Associate Professor in the Department of Surgery at Indiana University School of Medicine.

Zimmers’ expertise focuses on modeling muscle wasting in cancer and other diseases. She founded and directs the Center for Cachexia Research Innovation and Therapy at the Indiana University Simon Cancer Center and is the director of the interdisciplinary Center for Cachexia Research, Innovation and Therapy, part of the Midwest Cachexia Consortium. The goal of that group is to bring together various institutions, investigators and patients in the Midwest to find answers from basic and clinical studies on how the mystery that is cachexia can best be solved.

“Right now there is a very incomplete understanding of the biology of cancer-related cachexia, but compared to where we were just a few years ago, there have been some important findings that ultimately will hopefully help patients,” says Zimmers.

Understanding the Underlying Biology of Cachexia

Cachexia is not limited to those with pancreatic or other cancers. Individuals with AIDS, heart failure, dementia, and chronic kidney disease are also at risk, as well as those who suffer severe trauma or burns.

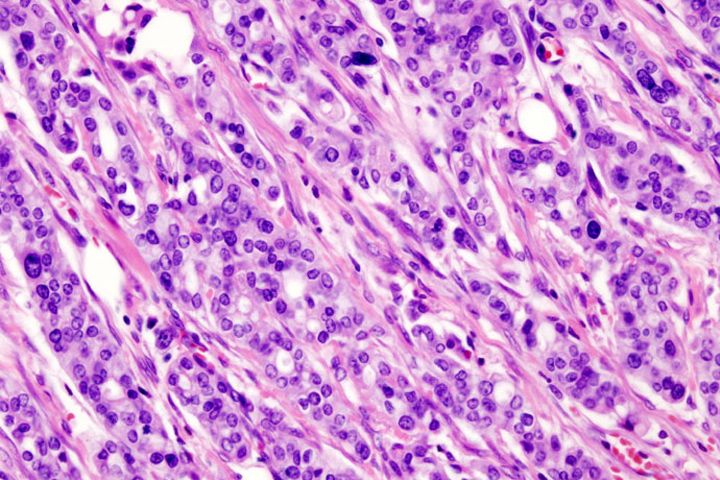

Scientists believe that multiple factors come into play in cachexia development. They have already identified genes that are more active in atrophying muscles than in normal ones. Numerous studies are suggesting that inflammation is a “unifying theme” for cachexia, Zimmers notes, adding that this inflammation may be caused, at least in part, by the body’s immune response to the pancreatic tumor.

The body produces what are called pro-inflammatory cytokines, molecules that help other cells communicate with each other during inflammation, infection, and trauma. Cytokines produced in response to the tumor influence tumor growth and modify the immune response, explains Zimmers. But they also change the body’s metabolism. This change can result in the breakdown of muscle proteins and fat.

Researchers are also looking at a family of proteins that includes activin and myostatin; both help regulate muscle growth. Some basic research work, including Zimmers’ own laboratory studies using an engineered form of a receptor for these two proteins, has shown that blocking the activity of myostatin and activin can affect cachexia. A few early-phase clinical trials have explored these pathways in patients. The hope is that in the near future this basic science will translate into clinical trials of more investigational drugs to slow the progression of cachexia or stop it altogether.

Hope for the Future

One of the best things a person with pancreatic cancer can do is to consult with a dietitian or other member of the medical team to formulate a plan of treatment for cachexia, says Zimmers. Although currently there is no one treatment that can stop the process, supportive care including exercise, common anti-inflammatory drugs, pancreatic enzymes, nutrition supplements, and appetite-stimulating medications may help some patients with tumor-induced weight loss.

Patients need to know that national conferences are being held to bring together not only the best minds in cachexia research. These events will also bring together patients who know first-hand the devastating effects of cachexia so doctors can learn from them.

“It’s important for us to learn from patients so that we design trials that are patient-focused,” says Zimmers, who is a member of the organizing committee for the 3rd Cancer Cachexia Conference in Washington, D.C., September 24-26, 2016. Interested patients can attend an informational breakfast to communicate their concerns to and learn from experts in the cancer cachexia field.

“These patients are fighting on two fronts. They are fighting a disease and they are fighting a side effect of that disease, which is cachexia,” Zimmers says. “I am very hopeful that we will find answers that will improve their lives.”