Overcoming Challenges to Vaccine Immunotherapy

Near the end of the 19th century, a physician by the name of William Coley made the first attempt to stimulate the immune system to help improve a cancer patient’s condition. At the time, it was a radical idea, met with skepticism and scorn, despite Coley reporting some good results.

Modern immunology shows that Coley’s principles of immune stimulation were indeed on target, and today the field of cancer immunology has become a highly sophisticated specialty. Indeed, cancer vaccines have caught the imagination of the public and of researchers who are investigating and developing these vaccine therapies. But the clinical translation of cancer vaccines into effective treatments has been challenging. Nonetheless, there have been some incredible breakthroughs.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved two prophylactic vaccines, meaning these vaccines can prevent cancer, including one for hepatitis B virus that can cause liver cancer and another for human papillomavirus, which accounts for about 70% of cervical cancers. More encouragingly, recent advances in cancer immunology have achieved clinical proof-of-concept for therapeutic cancer vaccines. For example, sipuleucel-T, an immune cell-based vaccine, resulted in increased overall survival in hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients. This led to FDA approval of this cancer treatment vaccine in 2010.

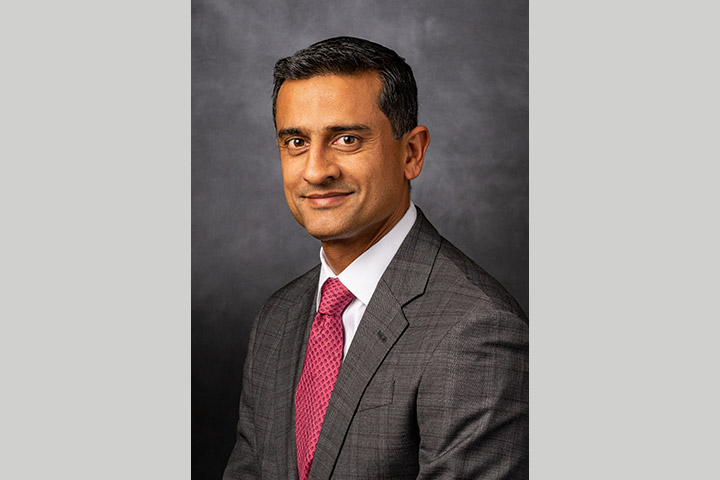

There is incredible excitement in the field, explains Dr. Elizabeth Jaffee, Associate Director, Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and Professor of Oncology at Johns Hopkins Medicine, in Baltimore, Maryland, and an international leader in the development of immune-based therapies for pancreatic and breast cancers.

“Right now surgery remains the only potentially curative option for pancreatic cancer patients, but about 80 percent of those patients don’t survive five years, which is why researchers like myself who work in the field of vaccine immunotherapy are cautiously optimistic that vaccines, in combination with other agents, will eventually help improve patient outcomes,” she says. Jaffee also leads the Stand Up To Cancer-Lustgarten Foundation Dream Team project called “Transforming Pancreatic Cancer to a Treatable Disease.”

Overcoming Challenges

One of the challenges is that pancreatic cancer tumors don’t typically respond to immunotherapy. That’s because these tumors develop deep within the body and surround themselves with a tough, fibrous capsule that’s difficult for drugs to pierce. This fibrous capsule also wards off the immune system’s T cells, our so-called “fighter” cells, which attack foreign invaders and cancer cells within the body.

Plus, pancreatic tumors are immunosuppressive. This means that their microenvironment—all the cells that make up the tumor—creates a barrier to effective immune surveillance by T cells, explains Jaffee, adding that T cells are somewhat tolerant of cancer cells and cancer cells are also smart and are able to evade the immune response.

“But that doesn’t mean that current issues can’t be overcome,” she continues. “We are learning more about the biology of pancreatic cancer all the time. And, as we learn more about the biology of pancreatic cancer we are working on methods to induce and enhance T cells, which are critical to producing a clinically beneficial response.”

This would be an important next step for immunotherapy for pancreatic cancers, and one way to achieve this is to reprogram the tumor microenvironment to better mount a more robust anti-cancer immune response, Jaffee says. Currently, trials are focusing on not only identifying and overcoming the immune pathways unique to pancreatic cancer, but also on using a T cell activating vaccine to try to prime the immune system to fight back.

Vaccines for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment

A vaccine called GVAX, developed by Jaffee and colleague Dr. Daniel Laheru, boosts the immune system, resulting in immune cells seeking out pancreatic cancer cells throughout the body. And, hopefully, destroying those cells.

In one study, GVAX was combined with the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide and a special bacterium that boosts the immune response. The result: researchers reported that those with metastatic pancreatic cancer who received the combination treatment had an overall improved survival with only limited side effects. Several other trials using GVAX, combined with other therapies, are ongoing.

Dr. Jaffee and her team are working on other vaccine approaches, including one that directs the immune system toward the KRAS mutation, which is common in premalignant lesions. This could be a possible pancreatic cancer prevention strategy for persons at high risk. And they are also studying a so-called neoadjuvant vaccine that is administered prior to surgery with additional injections later to further boost the immune response.

“We are making progress, but it’s going to take some time,” Jaffee explains. “We really owe a debt of gratitude for those patients enrolled in clinical trials. They know the research may not help them, but it may help others.”

She adds there have been some “amazing, and durable responses” for some vaccine trial participants. “That’s why we go on,” she says. “I want to see pancreatic cancer turned into a manageable disease, a treatable disease, and actually I would love to see a vaccine prevent the disease. That’s the Holy Grail for all cancers.”

To learn more about GVAX, read the stories “Exploring the Better Treatment for Stable Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer,” “Two Types of Immunotherapy for Surgically Removable Pancreatic Cancer,” and “Chemotherapy, Immunotherapy, and Radiation for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer.”