Tumor Genetics Research Brings Some Answers for Families at High Risk

Research on the genetics of pancreatic cancer is still somewhat in its infancy.

But ongoing work by genetic detectives like Gloria Petersen, Ph.D., Professor of Epidemiology at the Mayo Clinic, is paving the way for tests for earlier detection, risk assessment, personalized treatment, and preventive steps that people at high risk for the disease can take.

“There is still a lot we need to learn, but we are making progress,” says Petersen, who founded the PACGENE Consortium, a group of leading cancer institutions across the United States and Canada that are collaborating to identify susceptibility genes in high-risk familial pancreatic cancer, in those families with at least two affected first degree relatives with the disease.

What Has Been Learned about Tumor Genetics

Collaborative efforts in studying the genetics of pancreatic cancer have already yielded important information. Here are just a few findings:

- Individualizing Risk: Inherited pancreatic cancer can be caused by mutations, known as “germline” mutations, in a number of different genes. These mutations occur in egg or sperm cells and are passed on to every cell in an offspring’s body during reproduction. Today, those at risk of pancreatic cancer due to certain inherited genes can now be better informed of their risk. The genes that can confer inherited risk include BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and CDKN2A. Studies have also shown that certain hereditary colorectal cancer genes, specifically MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6, also increase the risk of pancreatic cancer.

- Risk Varies by Mutation: Genetic variants that are common may only increase a person’s risk of pancreatic cancer one or two percent, while more rare mutations can carry a higher lifetime risk of five to 30 percent.

- Other Factors Influence Risk: Studies have shown that about ten percent of people with pancreatic cancer carry the rarer mutations in genes like BRCA2, ATM, and PALB2. The remaining cases of pancreatic cancer may be linked to the lower-risk genes, lifestyle, or environmental causes, explains Petersen.

- Familial Pancreatic Cancer Is Not a One-Gene-Fits-All Scenario: Research shows that family members with familial pancreatic cancer may have a mutation in one gene, such as BRCA2. Another family may have a PALB2 mutation.

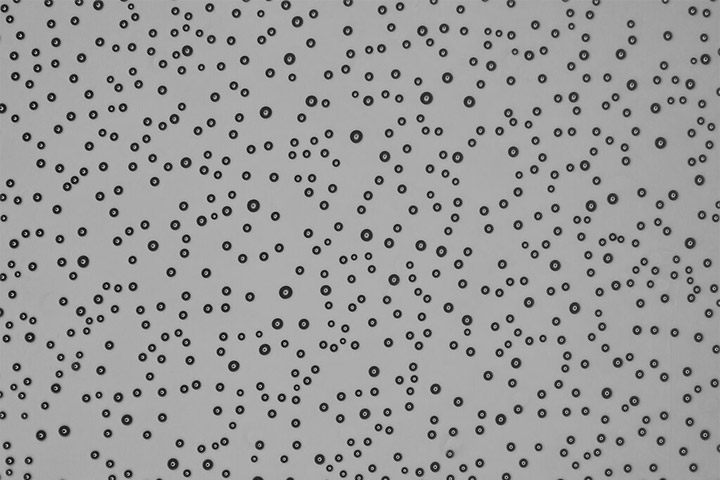

- New Information on Tumor Formation and Spread: Because the cells of pancreatic tumors can be vastly different in the same patient (meaning the tumor is heterogeneous) scientists have assumed there were many different acquired genetic mutations that caused tumor formation and spread. However, genetic research showed the same mutations are involved in driving the primary tumor and the metastases, potentially paving the way for targeted therapies to treat metastatic disease.

Moving Research from the Lab to the Clinic

“Getting a better understanding of the genes that could cause familial pancreatic cancer helps us not only quantify the risk of pancreatic cancer but also the risk of other cancers,” says Petersen, who is also the lead investigator of Mayo’s Pancreatic SPORE initiative, which is focused on the genetic and biological factors influencing pancreatic cancer. “The point of the research is to move the findings from the laboratory into the clinics so we can try to save lives by not only detecting cancer earlier, but also providing more individualized treatment.”

Indeed, individualized treatment does hold promise. Already, doctors know that some drugs seem to work better in patients whose tumors carry certain mutations. For example, one drug called erlotinib may work better in patients whose tumors have a particular change in a gene called EGFR.

To be clear, though, DNA is not always destiny. “Many people who carry mutations may not develop pancreatic cancer, but positive family history of pancreatic cancer is a consistent risk factor, with about a two-fold increased risk to first degree relatives” says Petersen, who along with co-investigator Ken Zaret, Ph.D., of the Penn Institute for Regenerative Medicine, developed a new blood test that uses two protein markers to pick up pancreatic cancer in its earliest, most treatable stages. The test is still being studied, but has shown 87 percent sensitivity, meaning that’s how often it can correctly identify someone with stage I or II pancreatic cancer. It also had 98 percent specificity, meaning the ability to accurately rule out cancer in a person who doesn’t have it.

Be Proactive

If you are concerned about your risk, there are steps you can take to reduce your risk. Among those risk-reducers are maintaining a healthy body weight, and quitting smoking, since tobacco users are about three times more likely to develop pancreatic cancer than non-smokers, says Petersen.

But if there is a significant family history of breast cancer or pancreatic cancer, there are tests available for the BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 genes. If there is a family history of melanoma and pancreatic cancer, testing is available for the p16 or CDKN2A gene. Some people may choose to participate in familial pancreatic cancer research registries.

The first step, though, is to speak to a cancer genetic counselor who can advise on the benefits as well as potential risks of genetic testing, explains Petersen, who is also researching the bioethical and behavioral implications of cancer genetic testing. A genetic counselor will go over the family history, see if there may be a hereditary component, and try to determine a person’s lifetime risk.

As to the future, Petersen is very hopeful. “Pancreatic cancer is a terrible disease, but I do absolutely believe that soon we will be better able to inform individuals about their risk,” she says. “Everything that we do adds to the body of knowledge about pancreatic cancer, and that’s why we do this.”