Pancreatic Cancer and Family History

Pancreatic cancer is a silent malady.

Most patients don’t realize they have the disease until it’s almost incurable. At this time, there are no recommended screening protocols for pancreatic cancer, as there are for breast and colon cancer. But experts agree that patient outcomes can be improved simply by paying attention.

Many pancreatic cancer patients report that doctors never asked about their family history of cancer prior to diagnosis. And that’s a problem, says Diane Simeone, M.D., Professor of Surgery and Pathology at New York University and Director of the Pancreatic Cancer Center.

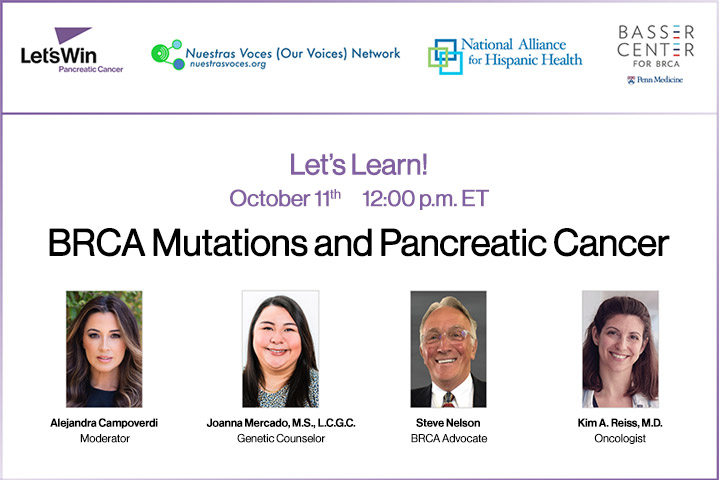

“A portion of the elevated risk of pancreatic cancer in families can be attributed to certain genetic syndromes that are linked with other forms of cancer, including melanoma, breast and colon cancers,” says Simeone. “Lynch syndrome, familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (or FAMMM syndrome), and the BRCA mutations, along with hereditary pancreatitis, all increase the risk of a patient developing pancreatic cancer.”

Now, there is a simple family history tool in the works. This tool will help doctors glean the information they need to ensure that everyone who has an elevated risk enrolls in a proper screening program. It would also allow those same people to have an opportunity to participate in clinical trials to test promising new blood-based biomarkers for the early detection of pancreatic cancer.

The Nuts and Bolts

To ensure doctors pick up on the family history link and possibly save lives, Simeone and her colleagues are developing a tablet-based electronic survey that patients can complete in 10 minutes while sitting in the waiting room. The project is funded by the Rolfe Foundation.

Since patients enter information electronically, the data can be integrated into their electronic charts. Many hospitals use electronic chart systems to allow doctors and staff to easily retrieve patient information. A bonus: Researchers will be better equipped to identify patients who are eligible to participate in clinical trials investigating early detection methods.

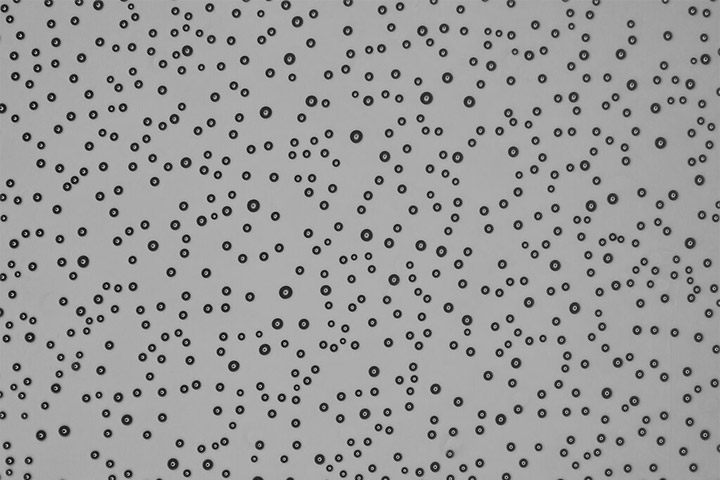

In fact, a blood test that can detect pancreatic cancer in its earliest stages is already in the works. “We have analyzed tumor cells in patients with pancreatic cancer and discovered that people from high-risk families have the same abnormal cells circulating in their blood, even if they have no evidence of pancreatic cancer,” says Simeone.

Since it’s difficult to access the pancreas, Simeone is hopeful these cells can serve as a beacon to find pancreatic cancer early in the disease process. Researchers are also studying different biomarkers (or abnormal cells that can be detected in the blood) to determine how they perform in different populations.

In addition to measuring circulating pancreatic cells, Simeone and her team are collaborating with others to test other biomarkers that show promise in early detection. One such biomarker platform has been developed by the Swedish company Immunovia, which measures a 29 protein immune-based signature in blood samples of individuals at risk for pancreatic cancer. “It will be very useful to set up a collaborative system where the performance of different biomarkers can be compared side-by-side,” Simeone notes. “This makes the most sense to move the field forward. We need to validate different tests, and determine their performance characteristics, such as the lead time between a positive test and evidence of an imaging abnormality.”

Another potential confounding factor may be that one biomarker might work well for patients with Lynch syndrome, for example, while another works better for patients with germline BRCA mutations or a family history of pancreatic cancer.

A Beacon of Hope

People who have a family history of cancer, particularly those who have watched other family members battle the disease, may be afraid to delve into their own personal risk of developing the disease. But according to Simeone, understanding your family history and getting the appropriate genetic tests has tremendous benefits.

“We have strong data that finding cancer at an early stage has a marked effect on survival,” says Simeone. “My personal goal is to ensure we achieve a 50 percent, five-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer over the next 10 years, and family history testing is a key part of that equation.”

Ultimately, Simeone hopes to develop a free app so anyone who wants to understand their risk for pancreatic cancer can access the app, answer a few basic questions and determine whether there’s a negligible worry or whether they should talk to their doctor or see a genetics counselor.

“Knowledge is power,” says Simeone. “If we know you’re at increased risk of pancreatic cancer, we can do something about it.”

To learn more about screening and early detection tests under development, read the stories “A Newly Identified Biomarker Panel Shows Promise in Earlier Pancreatic Cancer Detection” and “Developing a Screening Test for Pancreatic Cancer.”