Symptom Management for Pancreatic Cancer Patients

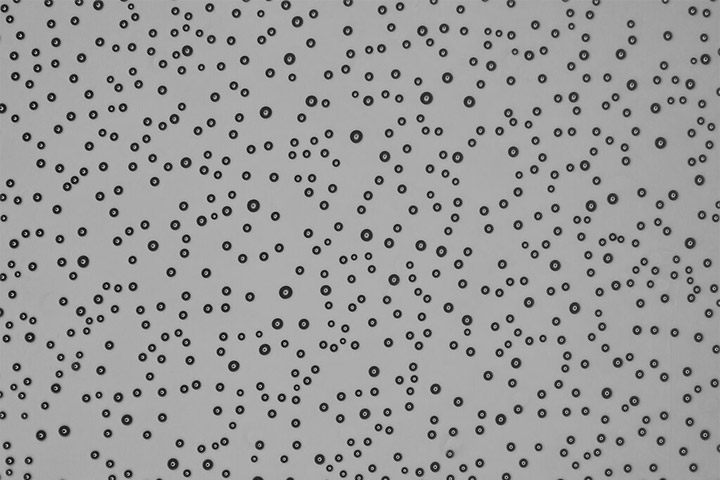

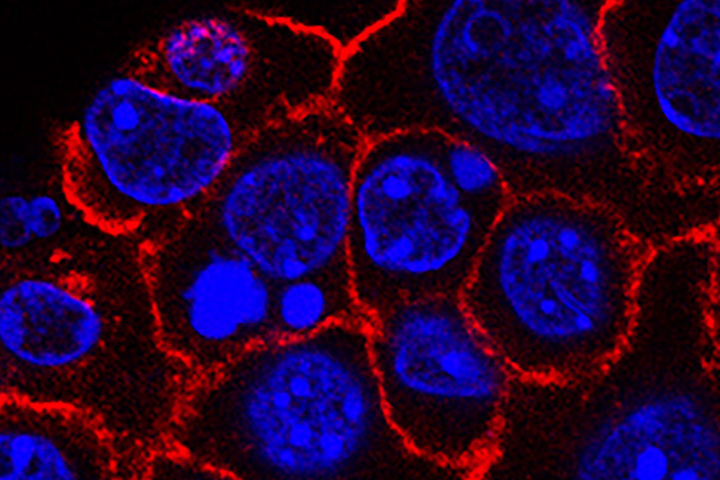

Min Yu,USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Pancreatic Desmoplasia

Managing the symptoms associated with pancreatic cancer and its therapies is an essential part of your care.

Besides improving your quality of life, feeling your best may even help you live longer. Do not be shy about reporting your symptoms to your doctor and caregivers. Your oncologist and his or her team should be able to help you manage symptoms of the cancer and the side effects of treatment.

Pain

Pain, particularly in the middle of your stomach and going to your back or around your middle like a “tire,” is a very common symptom of pancreatic cancer. This pain is caused by the proximity of the tumor next to your celiac nerve, which sends pain signals to your mid-section.

There are several techniques for pain control that you may want to talk to your oncologist about.

- Narcotics are a mainstay of pain control for pancreatic cancer. These drugs can provide enormous relief of your symptoms when used correctly. Many people will require both a long-acting twice daily narcotic to control baseline symptoms coupled with a short-acting pill that may be taken every few hours for breakthrough pain. Combination medications such as oxycodone/acetaminophen (Percocet and other brands) and hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin and other brands) and over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil) are not recommended, as these can cause other complications with your disease.

- Radiation therapy is sometimes used for tumors that are causing significant pain.

- A celiac plexus block numbs the celiac nerve near the pancreatic tumor. This procedure is similar to having a spinal tap: a small needle is inserted into your back and reaches the nerve. The procedure has potential for excellent pain control but is not always successful.

Fatigue

Fatigue is an extremely common and bothersome symptom of most cancers, and pancreatic cancer in particular. There are multiple potential causes: the illness itself, as a side effect of any number of the treatments you might be receiving, and emotional stress. Because of its multiple causes, fatigue can be difficult to manage.

For fatigue directly related to your cancer or its treatments, the stimulant methylphenidate (Ritalin and other brands) is sometimes used and can be helpful. Enrolling in a cancer-specific physical therapy program or simply trying to increase your physical activity level can also battle tiredness.

Fatigue related to emotional stress is normal when you are dealing with a serious medical diagnosis. It can be managed as part of a more extensive treatment for depression and anxiety, which is discussed below.

Steatorrhea

“Steatorrhea” is a term for the oily diarrhea that can sometimes accompany pancreatic cancer. You might notice bloating and gas after meals, stools that float in the toilet bowl, or a greasy film that accompanies your bowel movements. Steatorrhea is caused by impairment of the pancreas’ ability to process fats and oils. When fats that you eat are not properly absorbed by the digestive tract, they pass through the body fairly quickly and act as a laxative. This process can produce significant discomfort.

If you are having bloating, gas, or diarrhea, pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy can help. There are several versions on the market, all relatively equally effective. Once prescribed, the pills should be taken simultaneously with your meal to ensure they work properly. Do not be afraid to take more pills if you need them to control your symptoms; any excess is simply excreted by your body. Speak to your doctor about your progress, as he or she can adjust the number of pills you are taking to maximize your symptom control.

Poor Appetite

It is very common to struggle with appetite loss during the course of your illness. Emotional and physical factors (including chemotherapy and radiation) can cause food to entirely lose its appeal. Well-meaning friends and family may try to “force” food on you, knowing that nutrition is important, but it’s very hard to eat when you are feeling poorly.

It is a good idea to seek out the help of a nutritionist for general assistance and tips on how to get the most “bang for your buck” with the foods you can tolerate. Nutritional drinks—common brands include Ensure or Boost—may be a way for you to increase your caloric and vitamin intake without needing to digest solid food.

Some medications can also boost appetite. Mirtazapine (brand name: Remeron) is an antidepressant that can increase appetite and help you sleep. Dronabinol (brand name: Marinol) is synthetically manufactured THC (tetrahydrocannabinol, the active ingredient in marijuana) and can help boost appetite. Less commonly used medications include olanzapine (brand name: Zyprexa) and megesterol acetate (brand name: Megace). Your doctor can prescribe the most appropriate medication for you.

Depression and Anxiety

Being diagnosed with cancer is a life-changing event that can cause depression, anxiety, fatigue, and feelings of isolation. These feelings are normal given the gravity of the situation, and are sometimes termed an “adjustment disorder.”

There are several non-medical and medical strategies to help you manage these symptoms. These can include therapists, support groups, meditation, yoga, and antidepressants and antianxiety medications. Please do not be afraid to discuss your symptoms with your care team so that they can help find you the support that you need.

The physical symptoms of pancreatic cancer can be painful and tiresome. Beyond the physical discomfort, the illness can also cause significant emotional distress. Don’t be afraid to talk about your symptoms so that you receive maximal support.

The cancer journey is not walked by one person alone.

Kim A. Reiss, M.D., is an oncologist at the Abramson Cancer Center, at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.